Vault #11: Paper Son Soldiers

The History and Heroism of Brothers Benson and Richard Wong

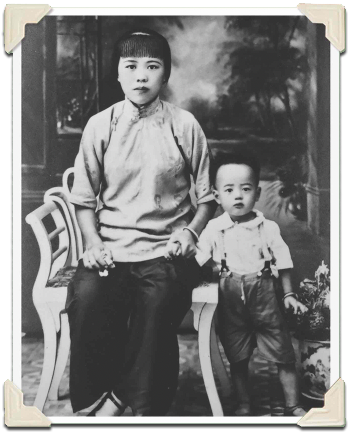

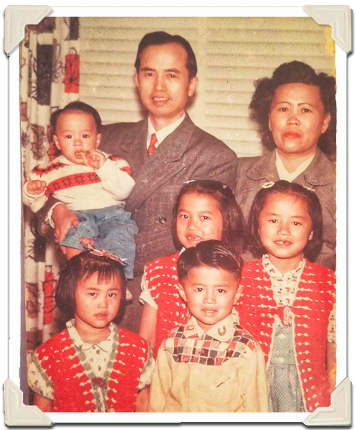

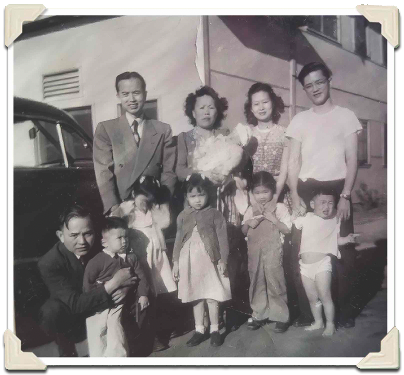

Family photo in Toishan, China (1920). A 4-year-old Benson Wong is circled in red.

“Paper Son Soldiers” tells the story of two brothers, Benson and Richard Wong, whose journey through Angel Island and enlistment in the US military demonstrate the commitment and sacrifice that many Chinese immigrants made to the United States during World War II. At a time when America’s exclusionary laws restricted immigrants from China and other Asian countries, “paper sons” found a pathway to citizenship through service to their adopted country.

We want to thank Benson, Richard, and the Wong family for sharing their stories and photographs with AIISF. Special thanks go to Arne JinAn Wong and Dr. Chun Yu for developing this story for AIISF and Anthony Wilson for helping bring the exhibit to the USS Hornet Sea, Air, & Space Museum. Learn more.

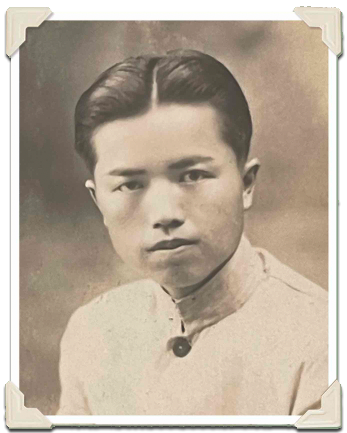

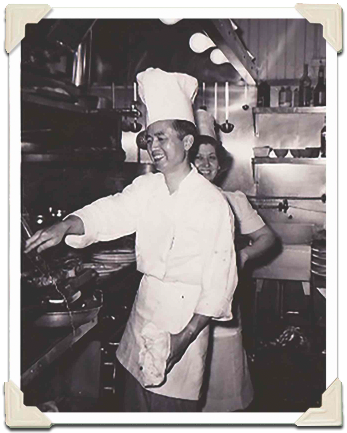

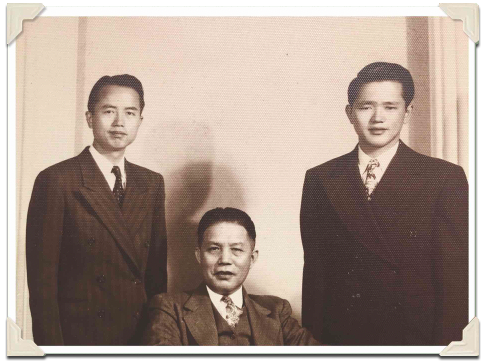

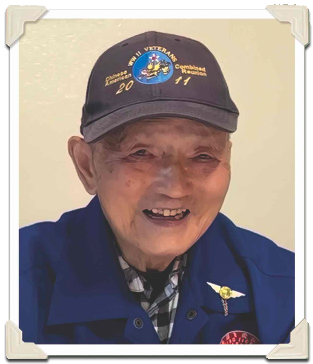

Benson JH Wong (1916-2021)

Angel Island, 1928

“My grandfather first came to America in 1909, and my father followed a few years later. My father was a merchant who could not sponsor a son to come to America due to the Chinese Exclusion Act. I had to come as a ‘paper son’ of a cousin of my father’s.

In 1906, the San Francisco earthquake burned down the city’s Hall of Records, which gave an opportunity for Chinese to add children to their family records. My relative claimed five sons living in China. I was one of them. My family paid $1,400 for my paper son certificate, which was two-years salary. I came to Angel Island in 1928 when I was 12 years old. I hadn’t seen my father or grandfather in many years since they left for America. On the ship to America, my paper father and I slept in the same bunkbed. I cried myself to sleep every night as I missed my mother, sisters, little brother, and my dog, who was my best friend. I had to memorize a book filled with details of my paper father’s life, family members, schools, house location, etc. When I was interrogated by the inspector, I made a mistake in describing our kitchen window, which almost cost me entrance to America. But I was able to correct it, and they let me through.”

Germany, 1944

“When I was stationed in Germany, I carried a typewriter instead of a rifle. They sent me to the field hospitals to help wounded soldiers who were unable to write home. I would sit with them and type whatever they wanted to say to their families. Mostly, the letters were going to the soldiers’ mothers. Many of the soldiers were about 18 years old. They were just kids.

It broke my heart to see them so badly wounded, blinded, with amputated limbs, and yet they had such a positive attitude and believed they had made a difference to the cause of the war against Hitler, and for the freedom for all the countries that were invaded. I also took care of a German family. I brought them food and supplies on a weekly basis from our commissary. I was invited to have dinner with them whenever I came over with food and supplies. Germany, at the end of the war, was devastated and in rubble and ruin. The civilians were left with nothing to live on, I felt so sorry for them, it reminded me of my own family in China.”

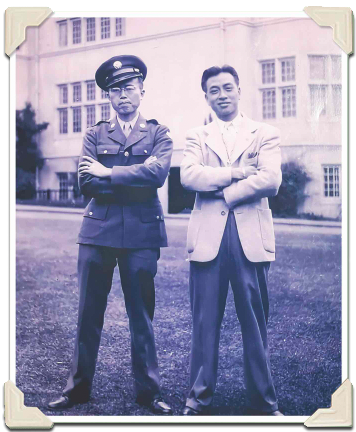

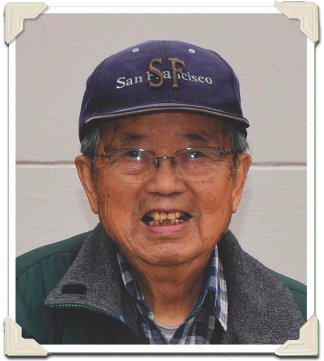

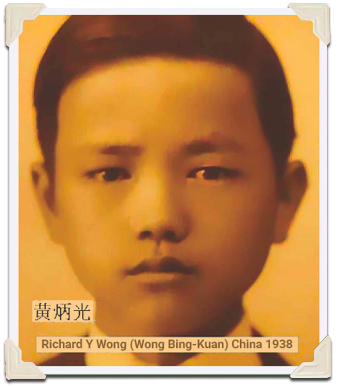

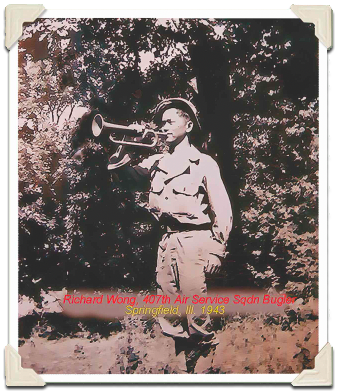

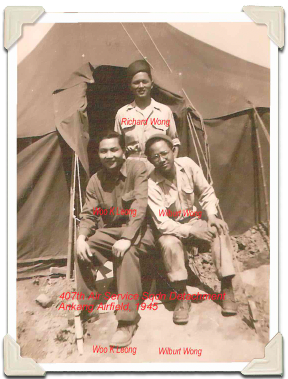

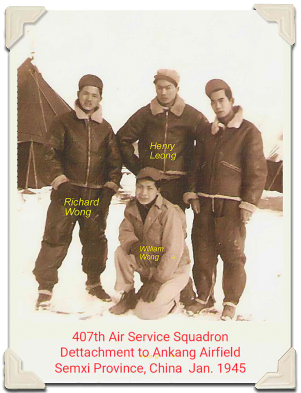

Richard Y. Wong (1921-)

Angel Island, 1939

“I came to America all by myself at the age of 17. When I arrived, there were probably a hundred Chinese immigrants at Angel Island. Tragically, some who had been detained for months to years committed suicide, feeling too ashamed to return to China. I arrived as a paper son to one of our relatives and had to memorize a book of notes that would help me through the interrogation process. I passed with flying colors!

My paper father put me on a train with some fried chicken to go to Minneapolis, where my real father was. With no knowledge of English, I had nothing to rely on except a dictionary. I followed my suitcase whenever the black porters carried it from train to train. One of them was very friendly and curious about where I came from, having never met a Chinese person. I thought he spoke Chinese when he offered me a cup of coffee, which is pronounced ‘coffee’ in Chinese too. The trip took three days, it was winter and snowing when I arrived. I had never been in snow before and was awestruck and speechless. At the station, my father and brother welcomed me to my new home and my new life in America.”

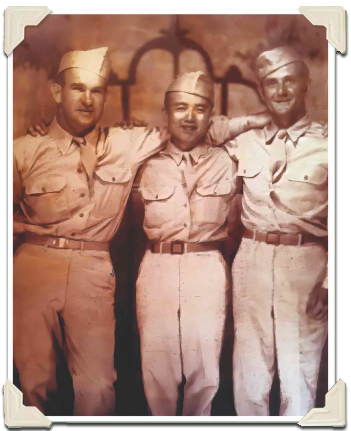

The Hump, 1944

“I served in the 14th Air Force Squadron, formerly known as the Flying Tigers. We flew over from Burma to China on a C47 transporter, following a treacherous route over the Himalayan Mountains called The Hump. With no reliable charts, radio navigation, or weather reports, many aircraft crashed with entire crews killed. You could see the wreckage of the planes glittering in the sun along the mountainside.

Our plane suddenly lurched down, we lost an engine. The captain ordered us to get ready to push our baggage and any excess weight out of the plane. We were ordered to jump with our parachutes if the plane didn’t level out. I had never used a parachute before. We were told to dive head first and count to 5 before pulling the ripcord. I had to avoid being hit by the propeller and the other 30 soldiers jumping. It was freezing cold. Everything was happening so fast that we had no time to think. As we opened the bay doors to dump our bags, the engine restarted. We all cheered with tears of joy. We made it to China!”