Vault #12: Administration Building

A Look Inside the Bureau of Immigration’s Headquarters on Angel Island

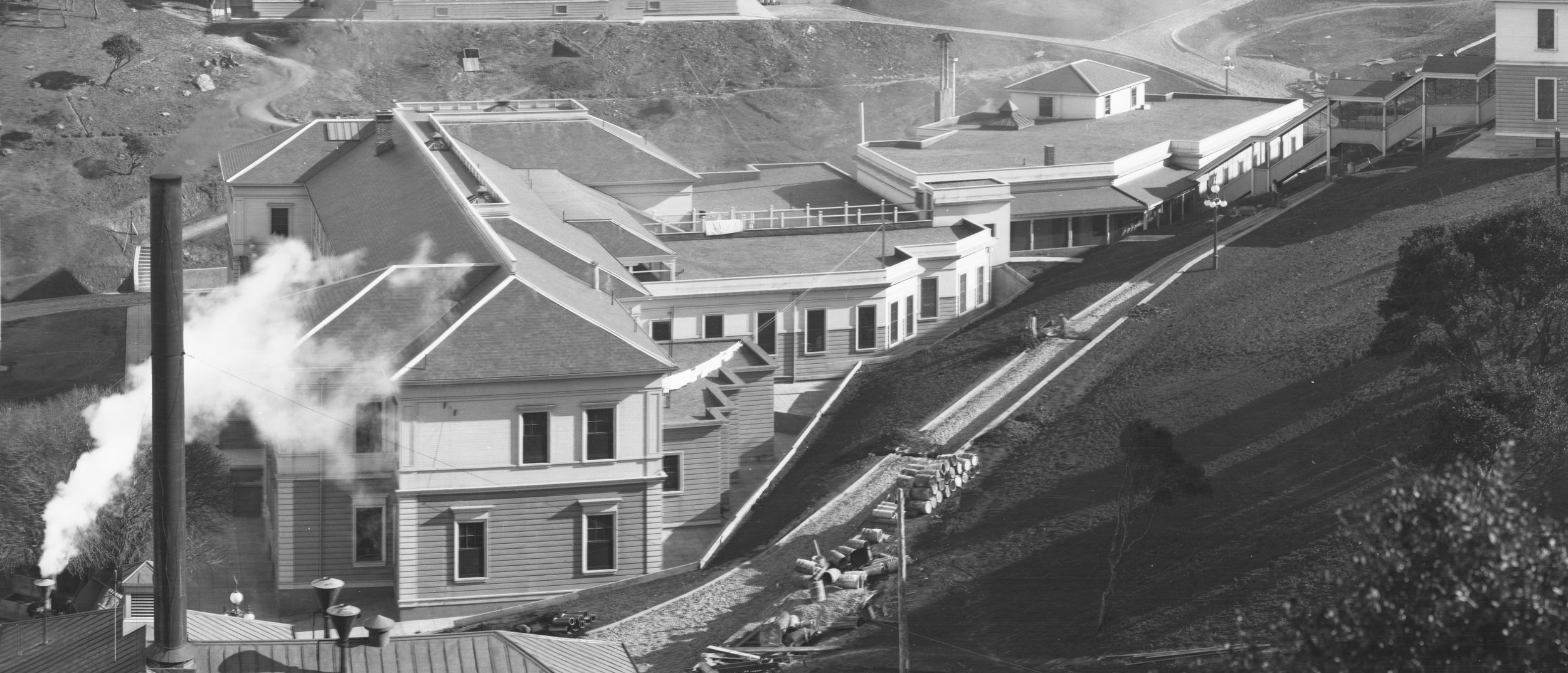

A view of the administration building at the US Immigration Station. This multi-purpose structure was a hub of activity from 1910 to 1940, when an electrical fire destroyed the building and hastened the site’s closure. Photo credit: California State Parks, Statewide Museum Collections Center (231-18-65).

Building a New Station

Oakland architect Walter Mathews designed the Immigration Station to be well-equipped to segregate, detain, and process hundreds of immigrants daily. In 1907, the San Francisco Chronicle celebrated Angel Island’s new facility as “the finest emigration station in the world,” touting that “newcomers from foreign shores will probably think they have struck paradise when they emerge from the steerage quarters of an ocean liner and land at the summer resort.”

This aspirational description was based on Mathews’ early architectural drawings, not the Station itself. In reality, the island was far from being a resort. Construction workers struggled to complete the site because of wharf damage, a lack of funds, and other issues related to building on barren and hilly terrain. The Great San Francisco Earthquake in 1906 also created labor and material shortages and delayed Mathews’ drawings by a month. To complicate matters, the first immigration commissioner, Hart H. North, used funds on embellishments like chandeliers, landscaping, and kitchen equipment before addressing critical issues like heating, plumbing, telephone service, and storage.

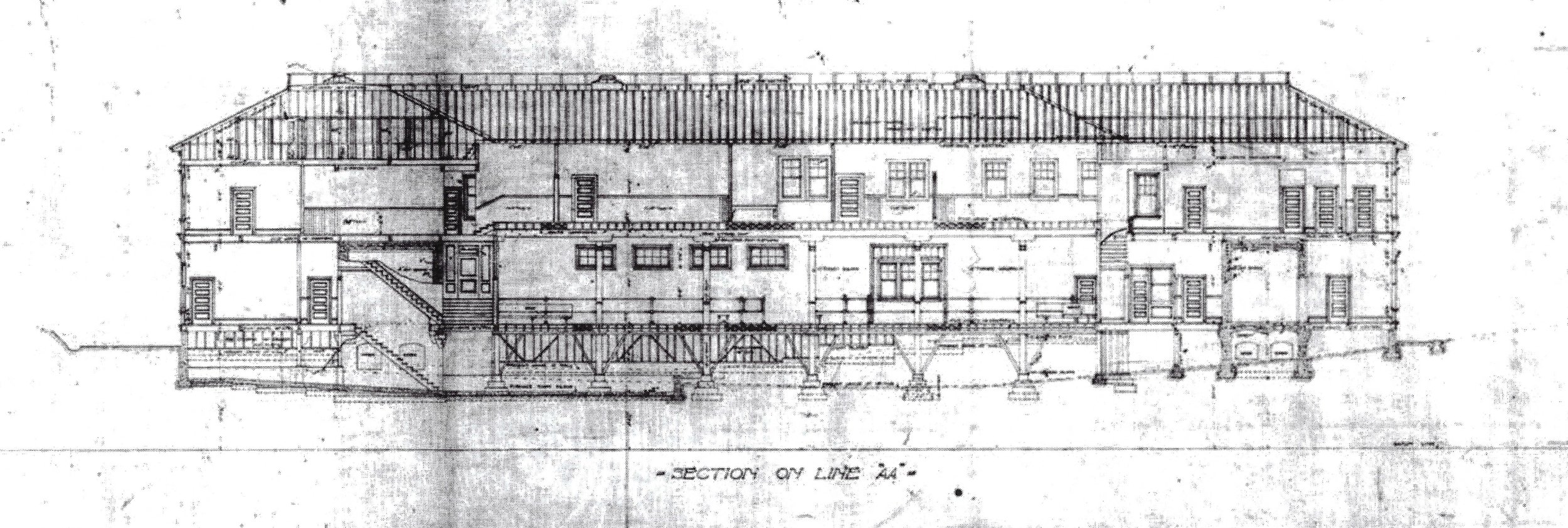

Interior elevation of the administration building from Walter Mathews’ site plan. The first floor shows the examination room (center) and Commissioner’s office (right). The second floor was primarily used as the women’s barracks. Photo credit: NARA, 1906.

Once principal construction was completed in 1908, the Station sat unoccupied for the next year and a half. Without additional money to furnish the buildings or supply them with power, the government’s new $500,000 facility was unusable. Only after US President William Howard Taft intervened in October 1909 more funds were released and the site completed. The Angel Island Immigration Station finally opened on January 21st of the following year.

-

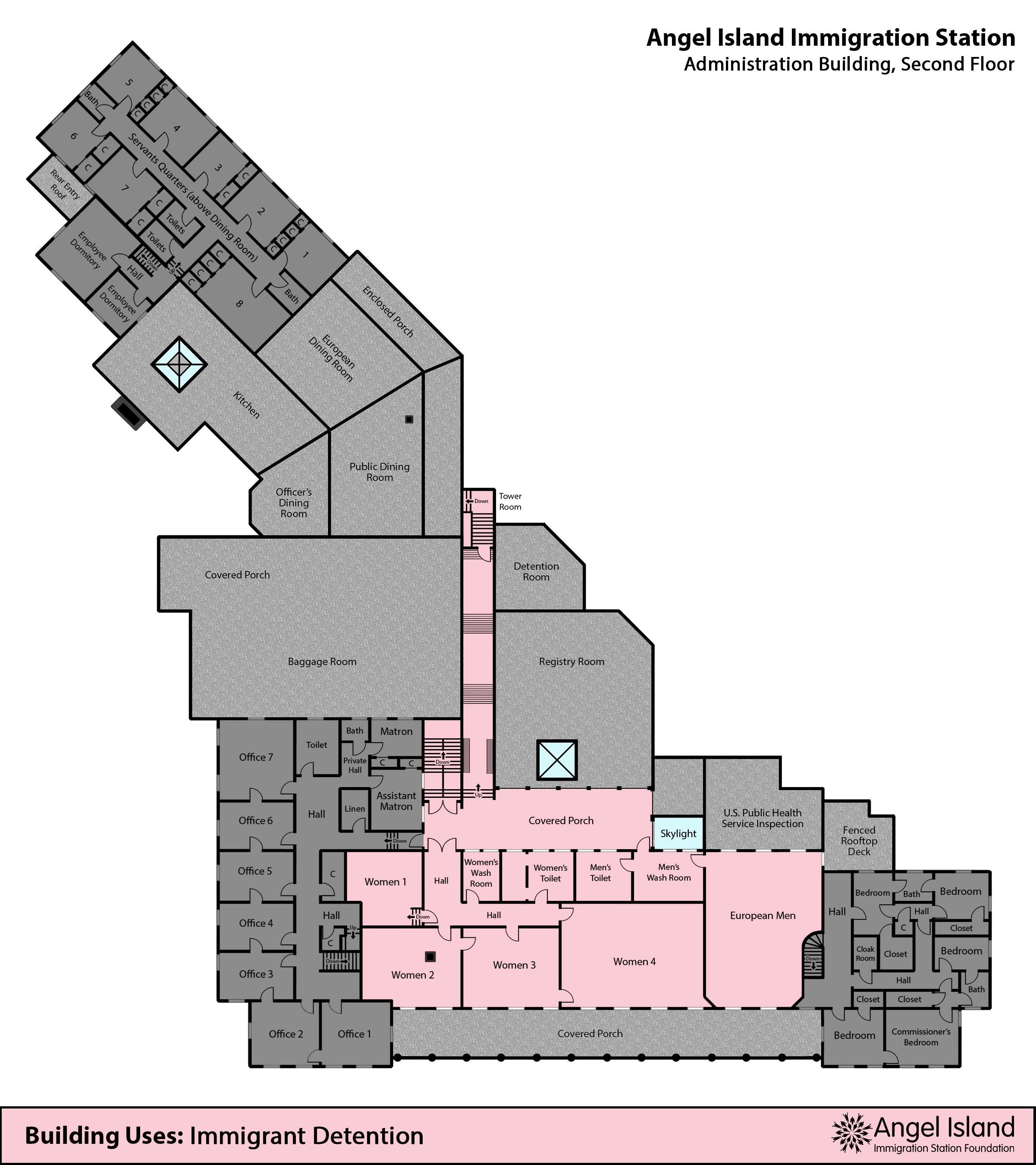

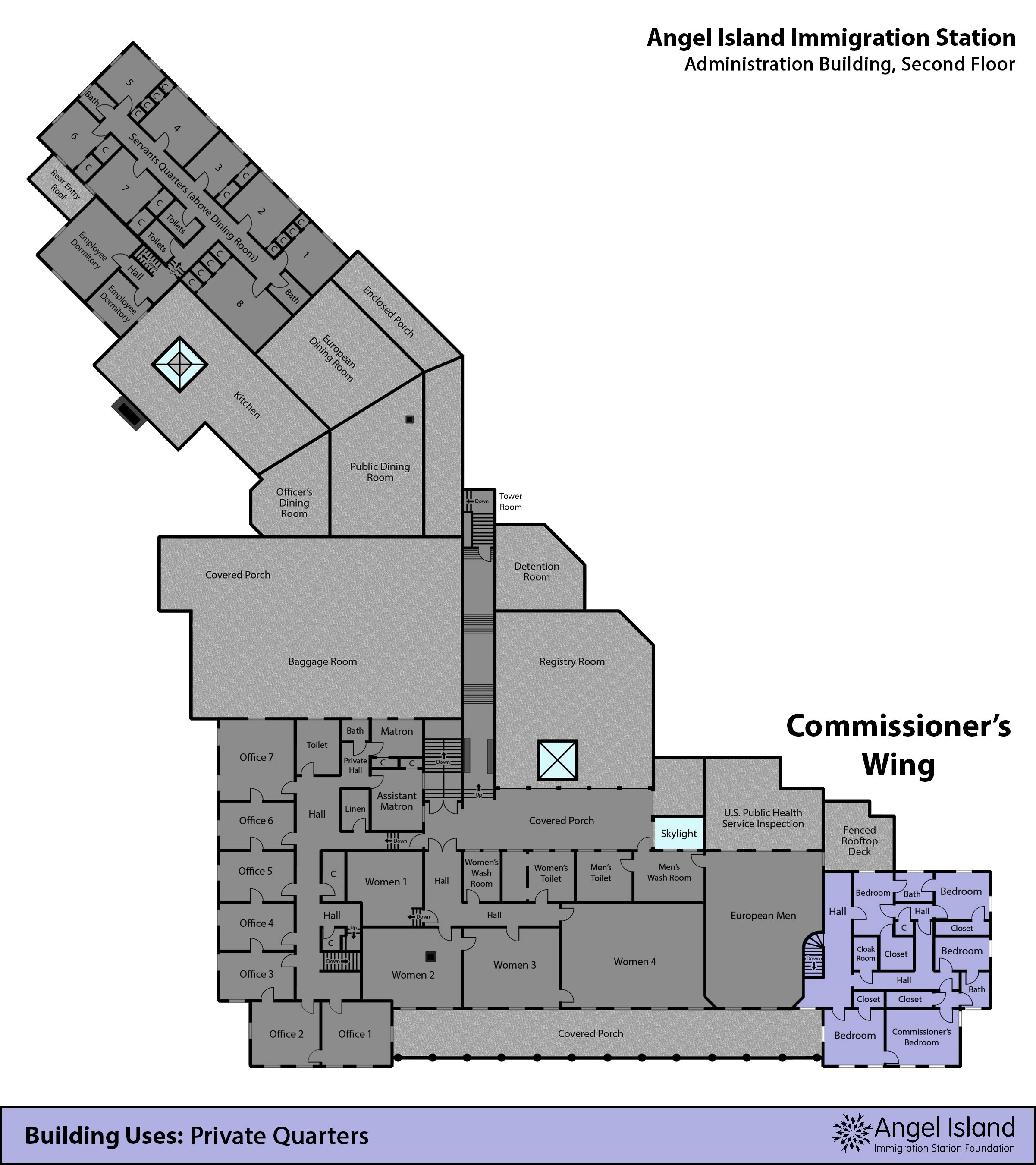

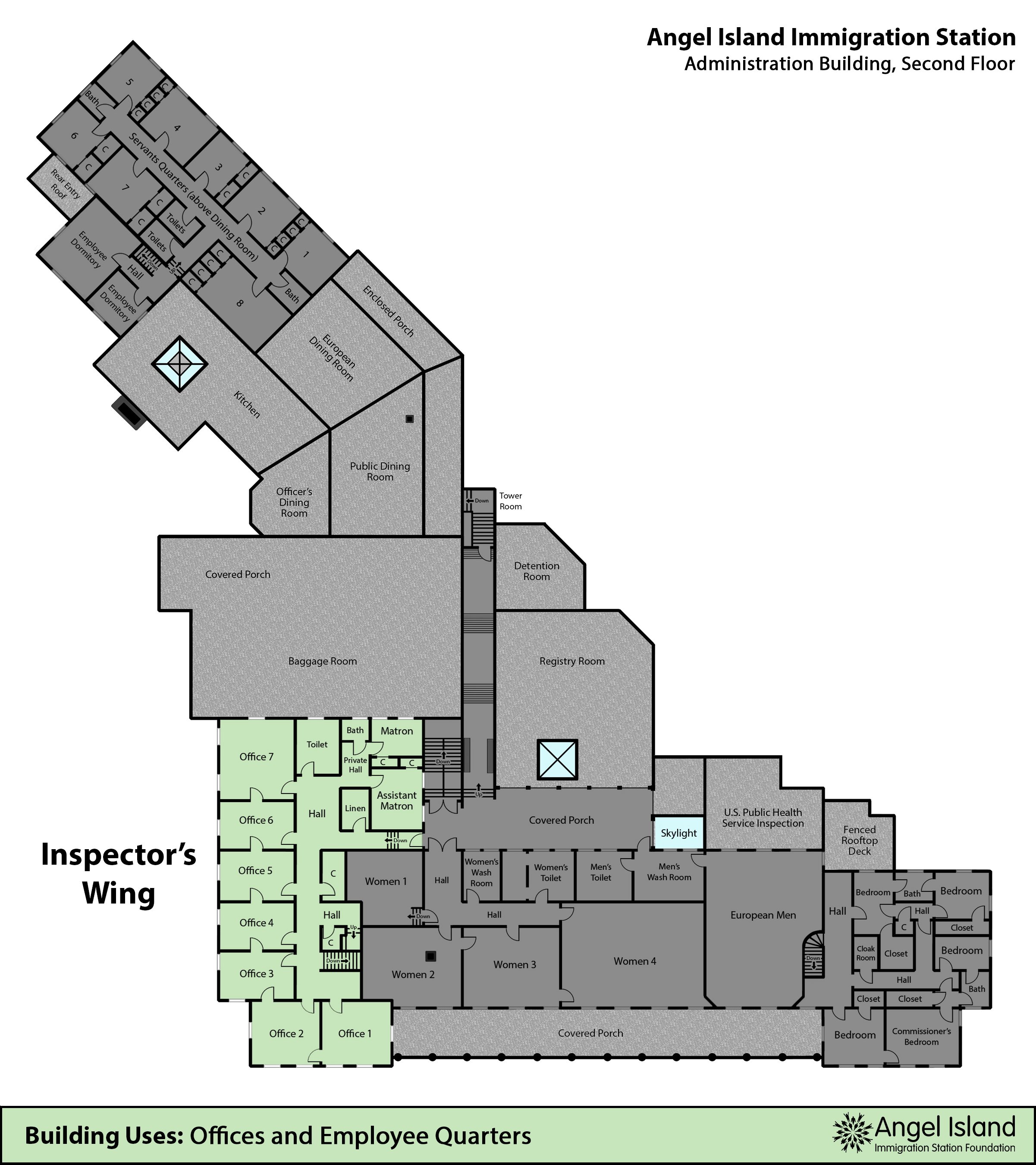

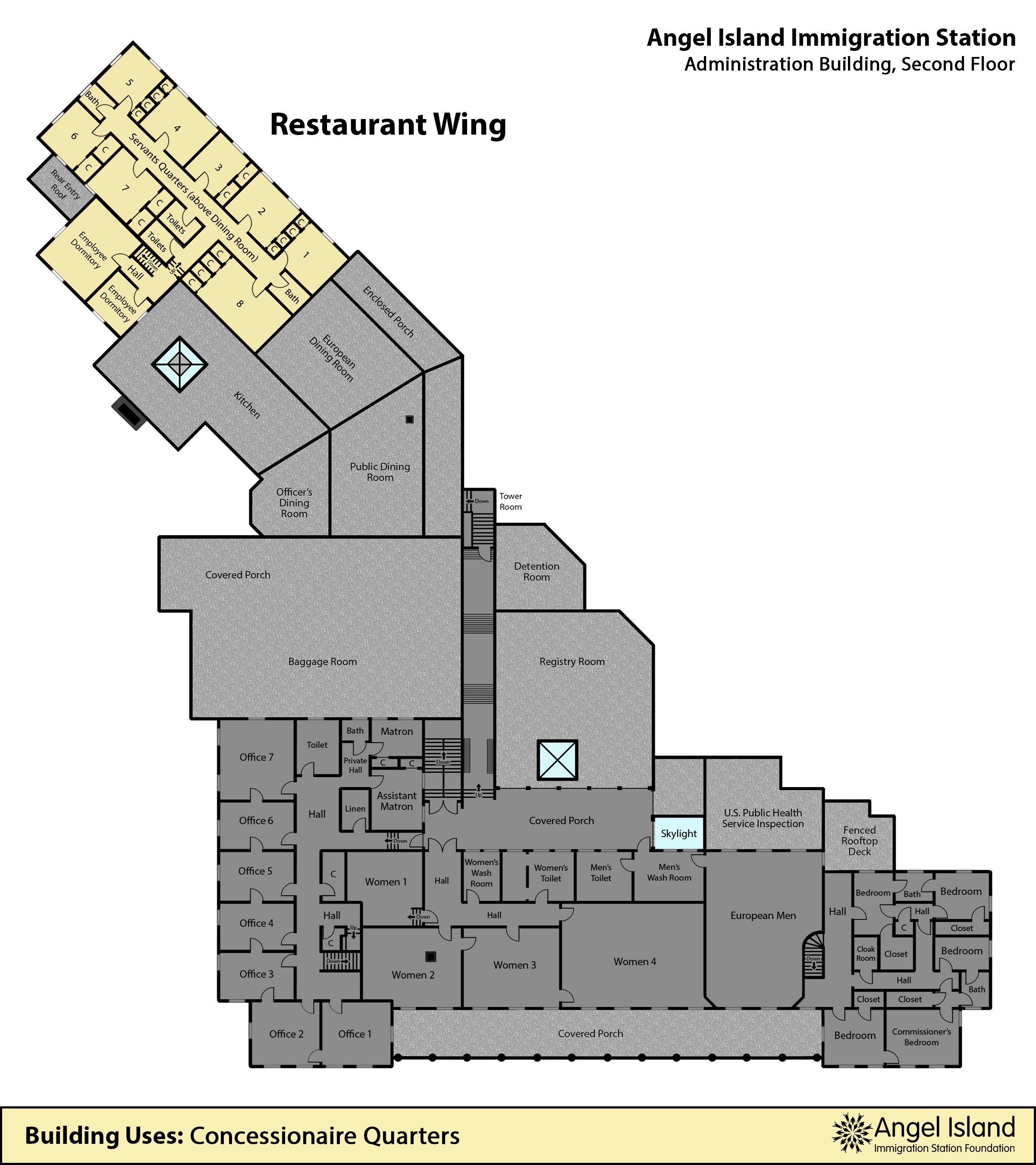

Rooms on the floor plan use labels taken directly from historical documents and references. With some exceptions, labels used for detained immigrants did not always reflect an individual’s country of origin or ethnicity. Inspectors sometimes assigned labels like “European” based on their observations, as with Margaret Lee Masters. These labels determined where an immigrant slept, ate, and received medical attention while on Angel Island.

The Bureau of Immigration’s San Francisco office used “European“ as an umbrella category for white detainees and other non-Asian immigrants, just as they sometimes used “Non-European” as a category for anyone who was not white. On Angel Island, “European” commonly applied to immigrants from Russia or Australia.

“Chinese and Japanese” (or occasionally “Asian”) were explicitly used for immigrants from those two countries. Approximately 180,000 detainees on Angel Island were from China or Japan. Although “Asian” often includes individuals from Korea and India, inscriptions found inside the barracks indicate immigrants from those countries slept in the same dormitories as European immigrants.

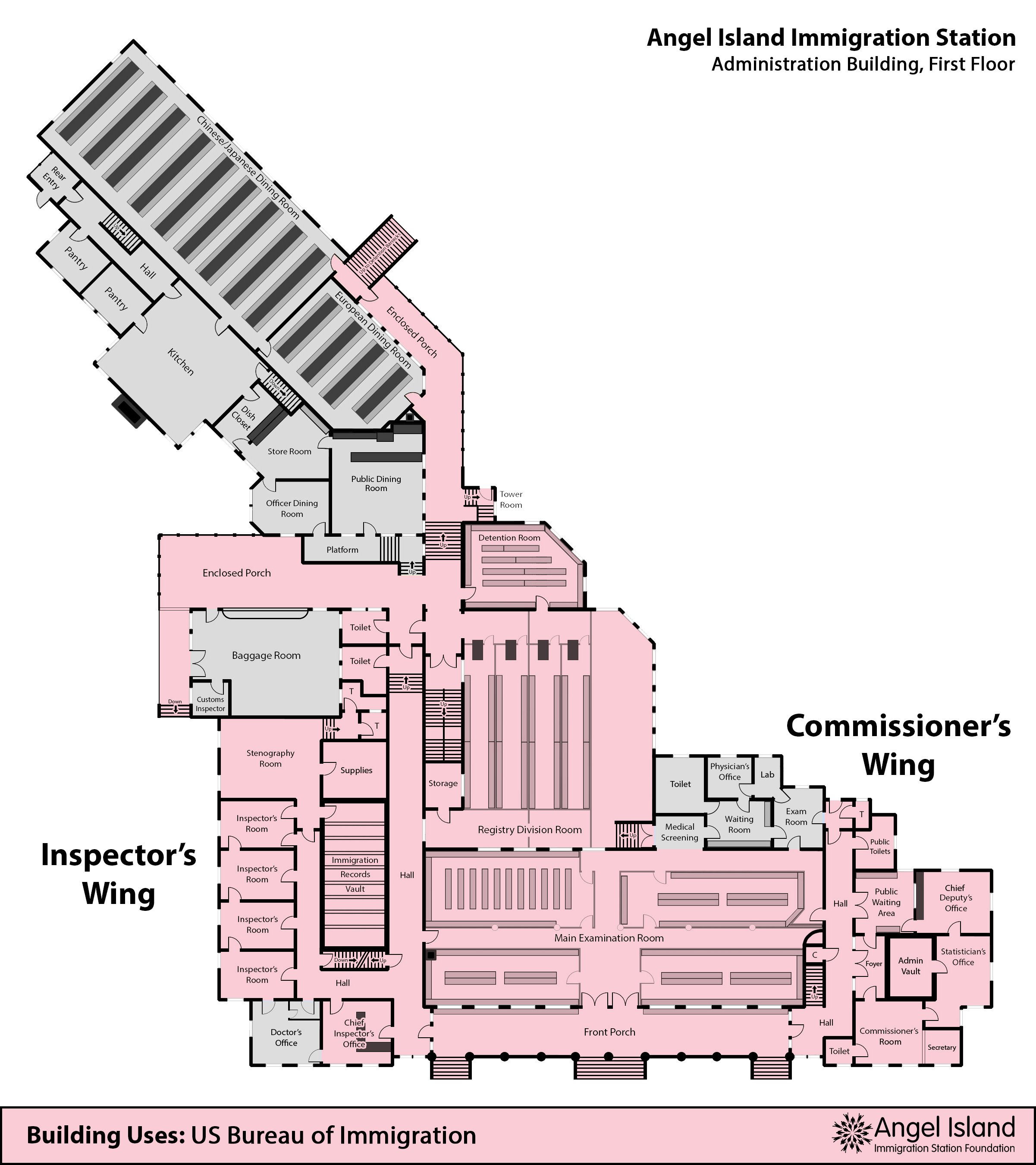

Building Uses

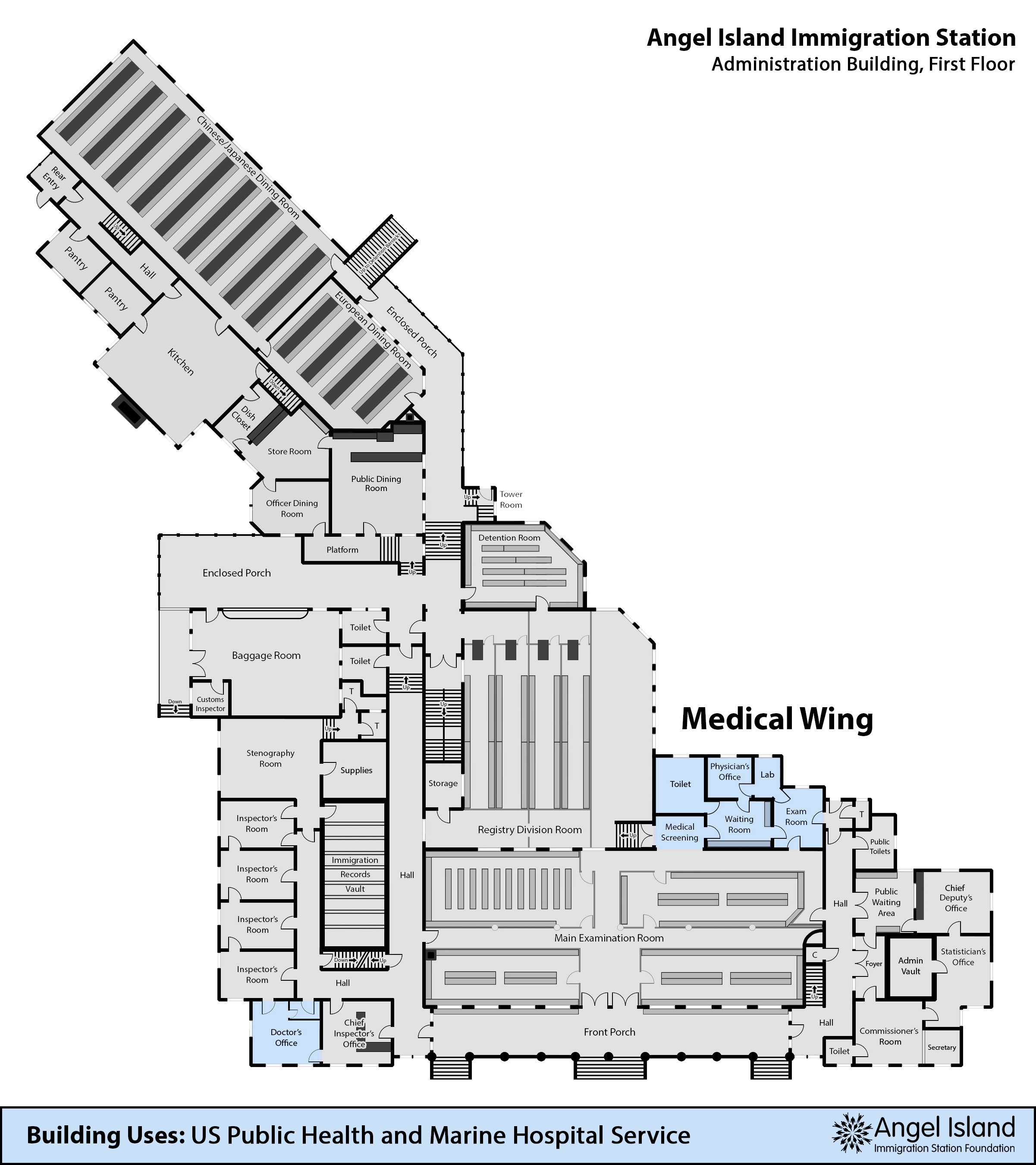

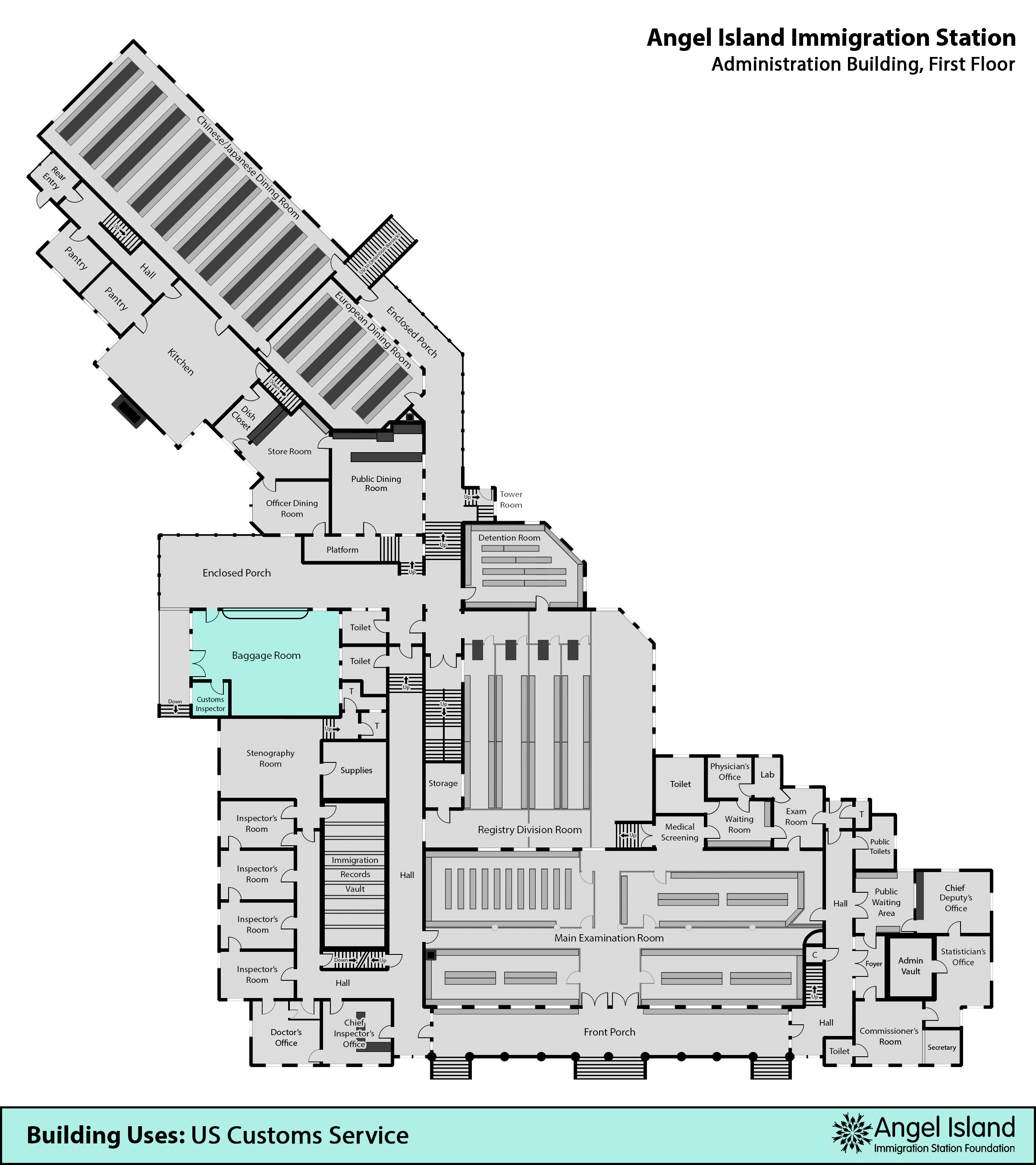

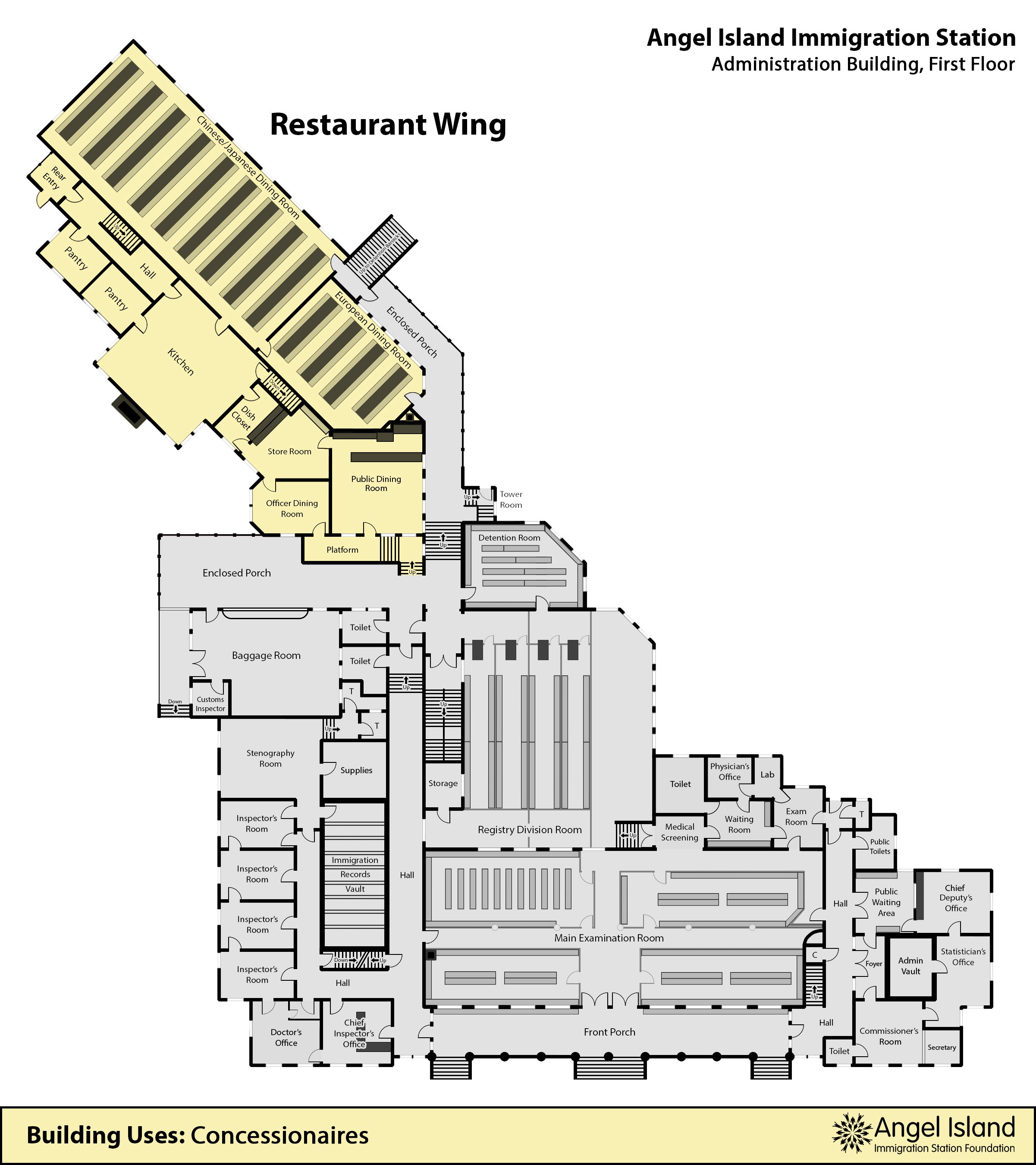

Though only traces of the administration building’s foundation remain today, it was once the center of operations and daily life at the Immigration Station. The building had offices for stenographers, inspectors, matrons, Customs agents, doctors, and the immigration commissioner. It also had rooms for medical examinations, detention, baggage, registration, sleeping, dining, and government records.

The Bureau of Immigration occupied a majority of the administration building. The remaining spaces were shared with cooperating agencies and concessionaires like the US Public Heath and Marine-Hospital Service, US Customs Service, US Bureau of Lighthouses, the crew of the Inspector (staff boat), and restaurant workers. All divisions collaborated to enforce America’s immigration laws and provide services for those at the Station.

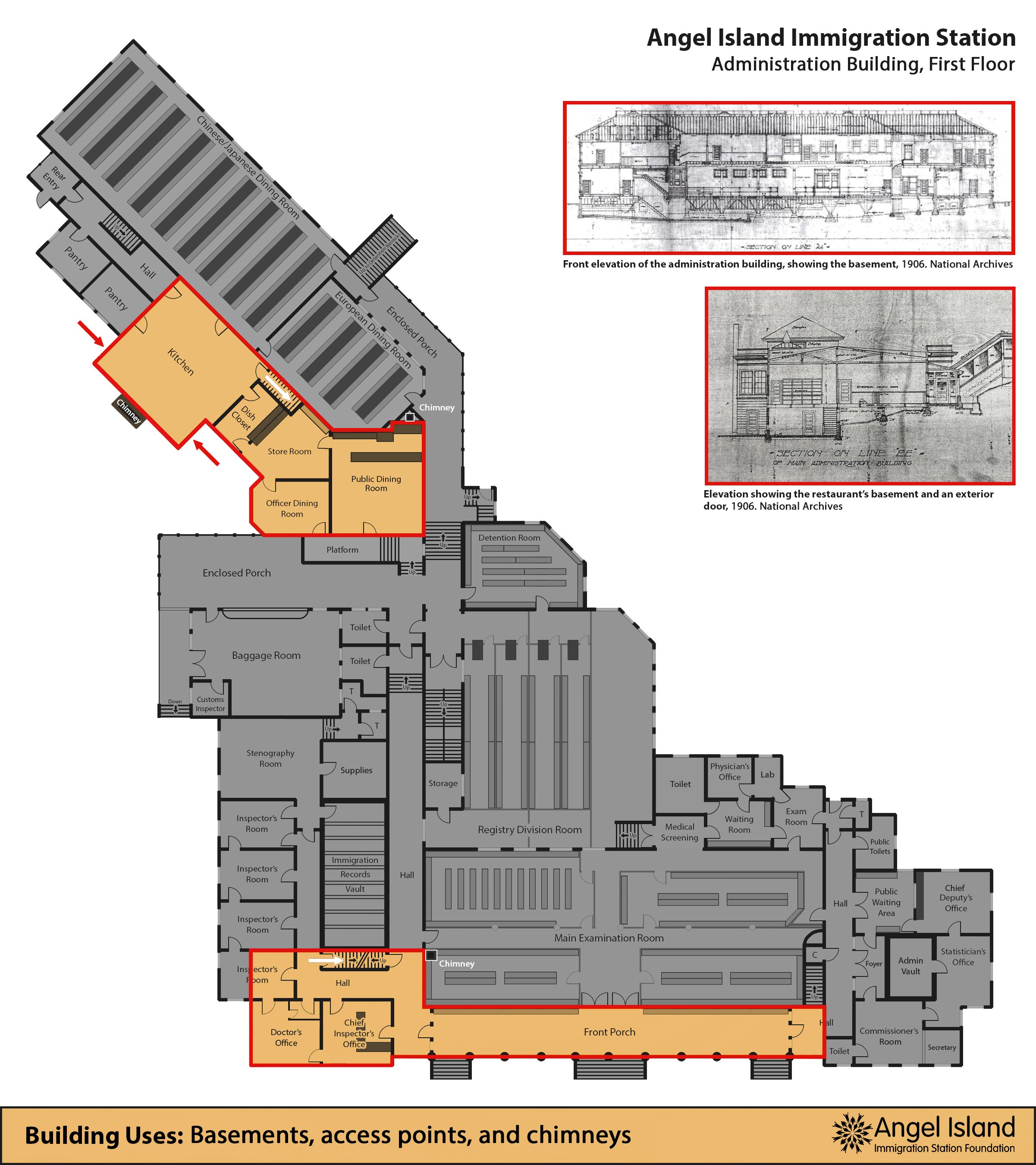

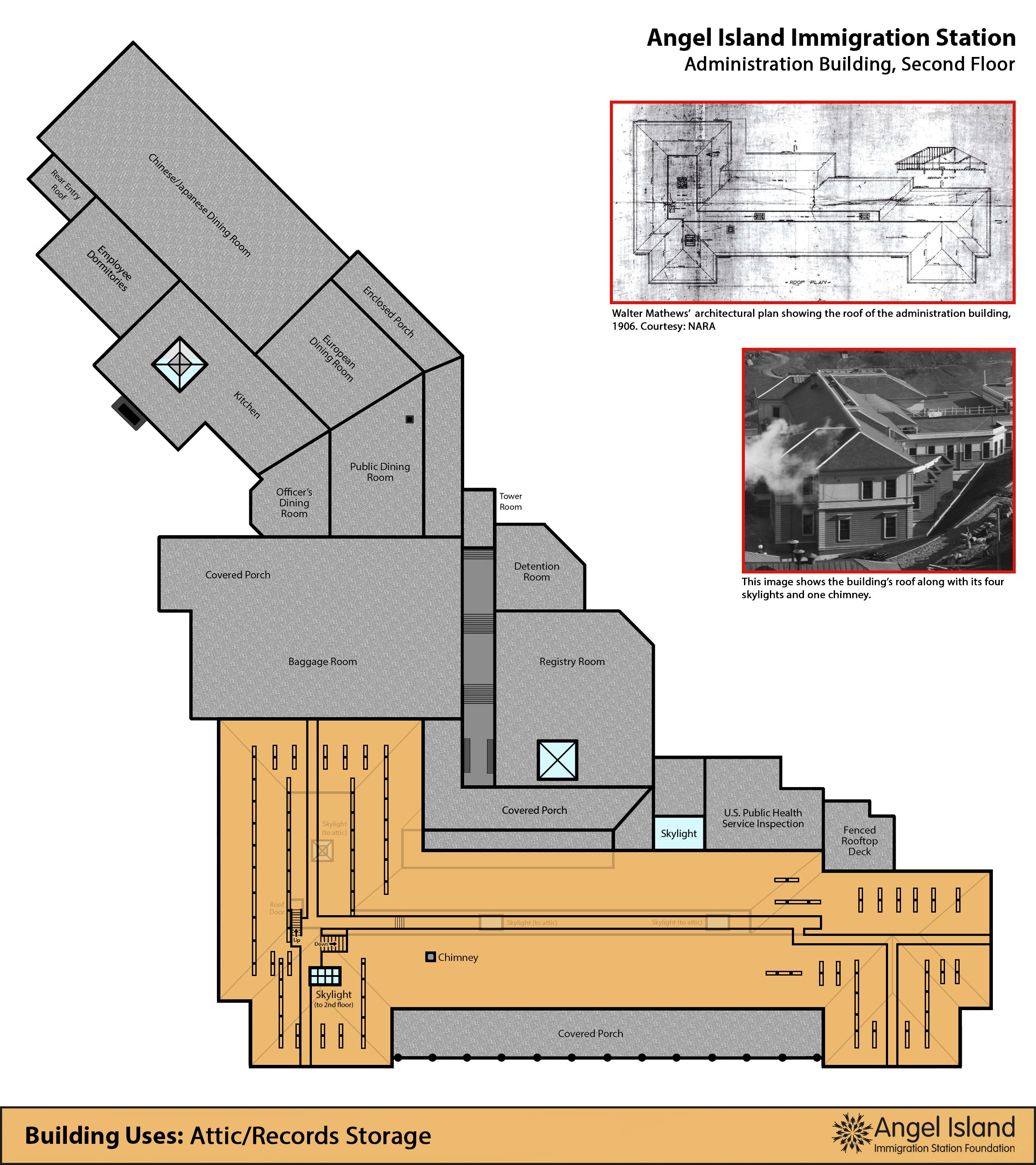

In addition to public areas, the administration building had auxiliary spaces, including an attic above the second-floor offices and two basements below the inspectors’ wing. Mathews’ elevation plans show both basements contained walls and doors, separating storage rooms from heating and refrigerator rooms.

The main administration building was the center of operations for the Bureau of Immigration. This photograph shows the examination room, where immigrants would be separated by race and gender before medical officers inspected them. Photo credit: NARA, c.1910.

By the Numbers

The following figures are based on a report sent by Commissioner Luther Steward in December 1910. His report was meant to illustrate the overall size of the Immigration Station so he could request additional support for cleaning and maintenance.

48,404 ft² of floor space (16,845 ft² in detention rooms)

33 baths, showers, and tubs

60 toilets and urinals

213 windows

164 electric light fixtures

57 steam radiators

66 cuspidors

9 lavatory basins

9 garbage cans

9 drinking fountains

2,511 ft² of wire grating

109 window gratings

1,239 linear feet of benches

1,044 ft² of desk and table surfaces

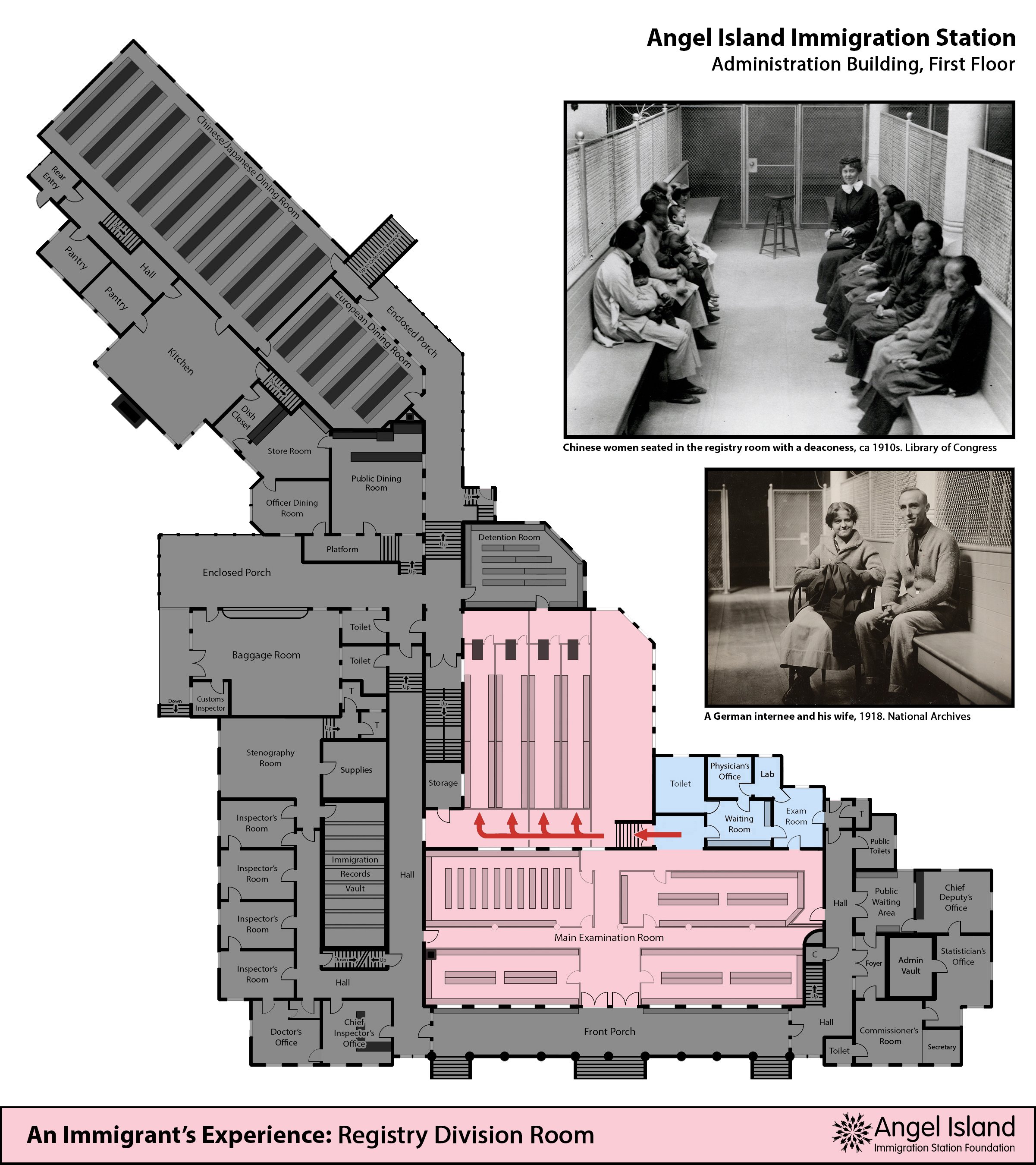

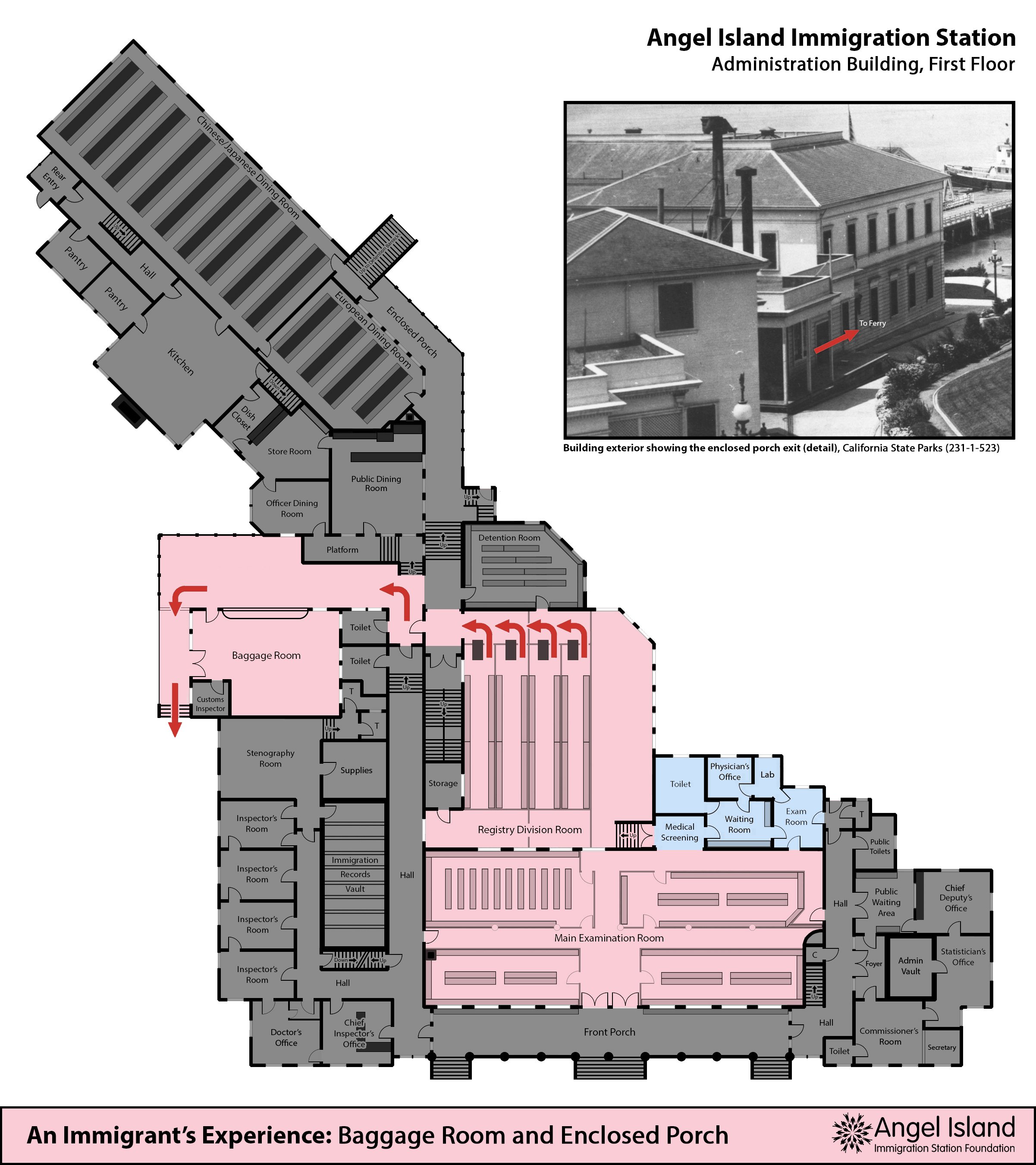

An Immigrant’s Experience

Every immigrant, non-citizen, or US resident sent to Angel Island entered the administration building. The San Francisco Chronicle offered a descriptive insight into the government’s immigrant intake procedures.

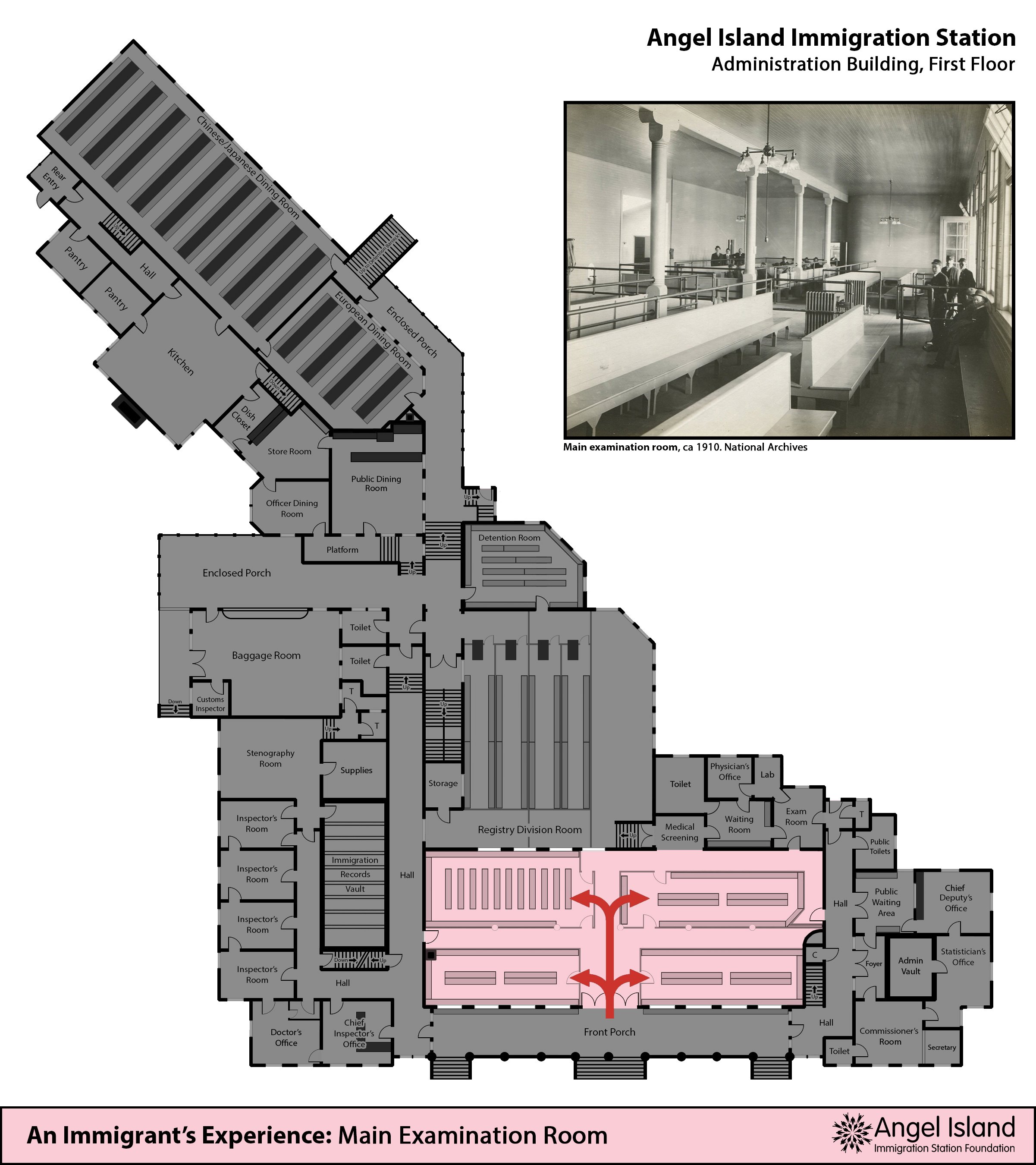

Main Examination Room

“Immigrants are first received and taken to an examination room divided into compartments separated by iron railings. The Chinese and Japanese are separated from the European and the women of the latter class are also received in a separate compartment.”Medical Screening

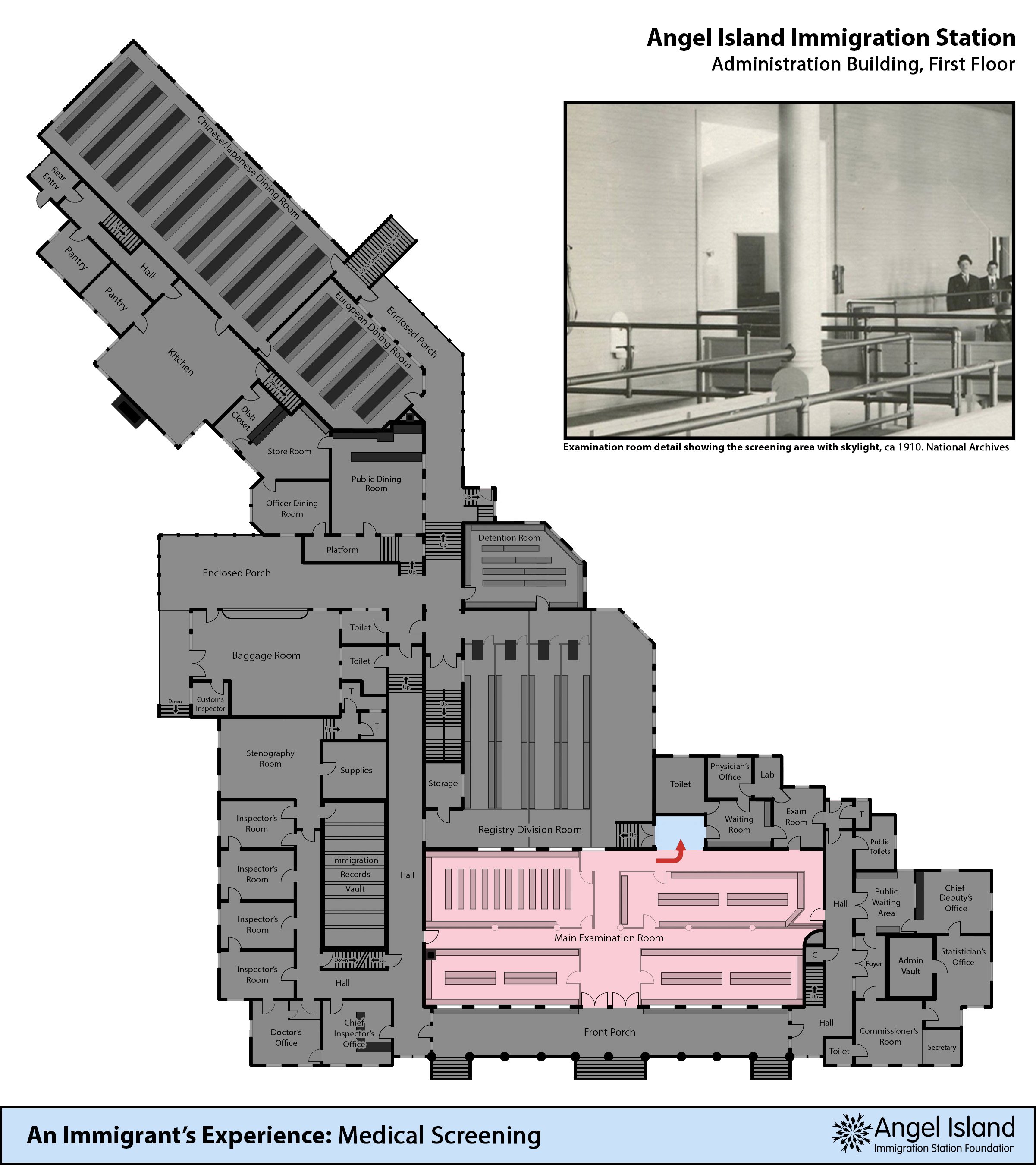

”Here under a skylight, the first test for trachoma (the dreaded Asiatic eye disease) is made and if suspicions are aroused…”Waiting Room

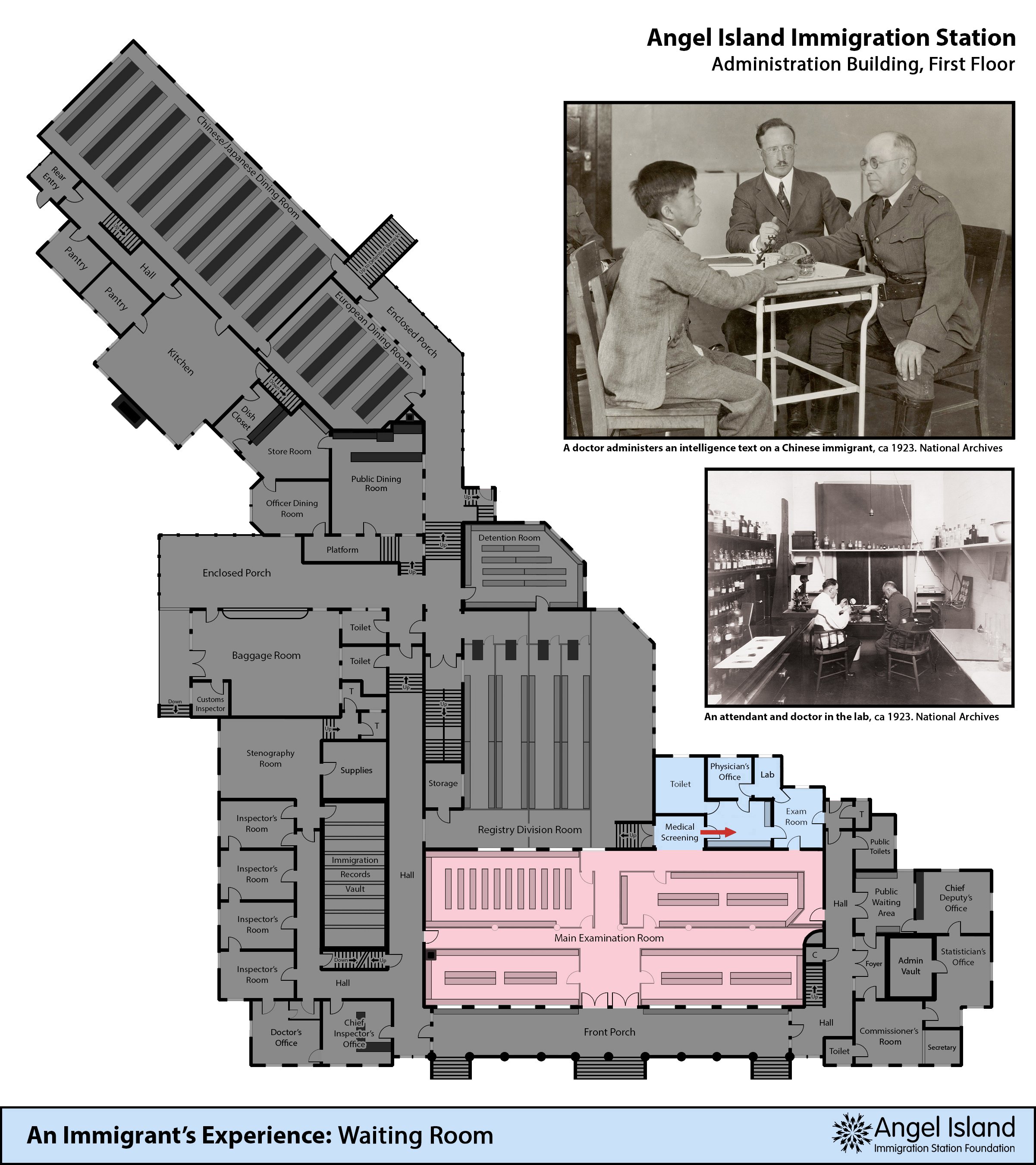

“…[immigrants] are assessed to the physician’s quarters where from a waiting room, they pass to a private examination room equipped with every late appliance for the examination of patients. If found to be diseased (unless the disease be contagious) the applicant is placed in the hospital and detained to await decontamination. If at the end of a certain time it is found that he cannot pass the physical requirements for admission to the country, he is deported. If suffering from a contagious disease he is of course deported at once unless his life would be endangered by such action.”Registry Division Room

”If the applicant passes the first test he goes into another room, divided into compartments according to his manifest, which gives his mental, moral, and financial qualifications. Here he is subjected to a further examination…”

Baggage Room and Enclosed Porch

”…and, if passed, goes to the [baggage] room, where he received his property and proceeds on his way, rejoicing, to the realms of Uncle Sam.”

The building’s first floor functioned as an administrative, investigative, and dining space, while the second floor served to detain immigrants, house employees, and provide additional office space for inspectors and matrons. This image, taken in 1910, provides a clear view of the building’s skylights, enclosed porches, and residential spaces. Photo courtesy: OpenSFHistory/wnp14.10845

Features of the Second Floor

The same San Francisco Chronicle article gives an overwhelming positive description of the facility, despite the article being written three years before the building had furnishings, electricity, employees, or its first immigrant arrival. In their description, the Chronicle stated the following.

Immigrant Detention

”Europeans sleep in a dormitory on the second floor of the main building and will have excellent accommodations, including baths, lavatories, and showers, a roof garden for daily exercises, and most of the conveniences of a first-class hotel.”Private Quarters

”On the same floor of the administration building are also sleeping quarters for visitors to the station, quarters for resident physicians and the Commissioner of Immigration. These are in a wing entirely separated from the immigrant quarters.”Offices and Employee Quarters

”On this floor [is] also a dormitory for the employees with all modern conveniences, the board of inquiry rooms for the examination of European immigrants, baths, lockers for both sexes, among the employees, etc.”Concessionaire Quarters

”The building is practically a hotel in all its appointments with kitchens, servants quarters, storerooms, and other departments of the great modern hostelry.”

In a follow-up article from the San Francisco Chronicle, they provide a more detailed description of these spaces.

“Upstairs are the dormitories; one for stenographers, one for employees, and the European quarters—women on one side, men on the other, each with large pleasant sitting rooms, washrooms with showers, and so on. There is also a large enclosed porch, where the babies and children may play in the sunshine.”

The administration building’s restaurant wing is visible in the foreground, with the detention barracks behind. The two buildings were connected by a covered staircase that led male immigrants into the dining rooms. At the right, the cage-like structure is a rooftop deck. It was where female immigrants and children exercised when they weren’t inside their dormitories. It was built sometime after 1913. Photo credit: NARA, undated.

Changes to the Building

The administration building needed functional upgrades as soon as it opened. The immigration commissioner and physician-in-charge filed numerous complaints regarding room usage, sanitation problems, and safety issues that complicated the work of inspectors and put detainees’ health at risk. To resolve this, architect William Otis Raiguel was hired to make structural improvements to the building and others at the site. Most documented changes occurred between 1910 and 1912, yet lesser-known alterations were made until at least 1937.

Without architectural plans showing the modifications to the building, it is difficult to know how the interior layout changed over time. The plans presented here were designed by referencing written requests from the commissioner and chief surgeon and descriptions provided by former detainees.

Opening in 1910

Assuming the 1906 plan accurately reflects how the building was used in 1910. However, employees likely deviated from the plan to address issues affecting the Bureau. Mathew’s plan showed several ambiguous spaces on the second floor, some of which were described in internal government correspondence. The following information represents what is known about the second-floor rooms.

Immigrant Detention

When originally designed, the dormitories and bathroom facilities were built into a 3,040 ft² space.

Private Quarters

There was a 1,500ft², four-bedroom, two-bath suite for the commissioner (or acting commissioner). It was accessible via a private interior stairway on the west side of the building.Offices and Employee Quarters

Above the inspector’s wing, on the second floor, was a set of seven offices and staff toilets. An interior stairway led from the central hall on the ground floor to the offices above. A matron and assistant matron’s 300 ft² residence was located in this area.Concessionaire Quarters

One of the two rooms had eight beds in the sleeping quarters above the kitchen, and there were no bathing facilities. The restaurant staff occupied one room, and the crew from the cutter Inspector occupied the other.

Changes by 1912

A year after opening, the building experienced a series of alterations and upgrades that reduced crowding on the second floor and created a more efficient work environment for employees. The most significant changes occurred in 1911 and 1912 when Washington D.C. supported the San Francisco bureau’s requests.

Foyer (First Floor)

Walls were removed in the commissioner’s wing for increased access to public areas.Toilets (First Floor)

Both doctor’s offices were removed from the building to accommodate another toilet in the examination room and a fifth inspector’s room in the opposite wing.Registry Division Offices (First Floor)

Additional offices were built in the vacant space in the registry room. Their use wasn’t documented, but inspectors likely held interrogations or hearings in these offices.Dining Rooms (First Floor)

Several changes were made to the public dining room. Furniture was removed, and a wall was knocked down to accommodate visitors. The public dining room was later utilized for the deportation hearing for union leader Harry Bridges in 1939.Concessionaire Quarters (First and Second Floor)

After Dr. Glover complained about the inadequacies of the upstairs quarters, workers were relocated to the baggage room on the first floor. The Bureau also abandoned the proposed “servant quarters” above the Chinese and Japanese dining room.Inspectors’ Rooms (First and Second Floor)

A commissioner report indicated that Asian interrogations were conducted on the first floor. On the second floor, janitors’ and watchmen’s dormitories were removed to accommodate European immigrant inspection.Board of Special Inquiry Rooms (First and Second Floor)

The building’s former detention room was converted into two hearing rooms—where immigrants had their cases decided by the Bureau of Immigration. Two additional hearing rooms were added to the northeast corner of the second floor.Private Quarters (Second Floor)

Throughout 1911 and 1912, the second-floor quarters were used as offices for the commissioner and assistant commissioner.Immigrant Detention (Second Floor)

Detention quarters were subdivided into smaller rooms to segregate races and classes. In late 1911, Chinese and Japanese women were moved from the barracks into the administration building. Research indicates the building had four women dormitories—Chinese, Japanese, European, and detained women pending deportation or trial. Later, an additional dormitory was identified for “Spanish” women, who would have arrived from Central and South America and the US southern border. Other changes included enclosing the European men’s sitting room, expanding the toilet facilities for the women, and closing the openings between dormitories and sitting rooms.

Changes after 1912

Records regarding additional construction and room assignments were destroyed in the 1940 administration building fire. An inventory of government records from June 1940 briefly mentions a photography “dark room” inside the building—possibly used to create certificates of identity for detained immigrants. Many changes were related to the functional uses of offices and dormitories. Some living quarters were demolished, and in some cases, new ones were added. Additional toilets for staff and immigrants accounted for most of the remodeling.

Concessionaire Quarters (First and Second Floor)

By 1913, restaurant workers and ferry crew had been moved out of the administration building. The former kitchen quarters were converted into office space, and the old baggage room became secondary records storage. According to the 1920 US Census, the kitchen offices had been reclaimed as housing, with restaurant manager Kenneth Echols and his wife residing there.Upstairs Offices (Second Floor)

There were only a few documented changes to the inspectors’ wing. The office space likely remained inspector rooms, but documentation suggests that the two northernmost rooms were converted to typing rooms for stenographers, and one room became an office for Deaconess Katharine Maurer.Private and First-Class Quarters (Second Floor)

By April 1913, the assistant commissioner had vacated his quarters. A room was converted to living quarters for the night watchman, with the others becoming rooms for first-class passengers detained on the island.Immigrant Detention (Second Floor)

The most significant changes post-1912 occurred in immigrant detention. A rooftop deck was built to give children an outdoor space to play, and after World War I, the Bureau enclosed the covered porch. This area became a multipurpose room where women could gather, attend classes, and participate in activities. An annex structure was built onto one of the dormitories later, but its use wasn’t documented.

The August 1940 fire heralded the end of the US Immigration Station on Angel Island. The Station remained open at the site until the last immigrants were transferred off the island on November 5. While countless immigration files were destroyed, there was fortunately no loss of life. This image shows the administration building on the morning of August 13. The spacious attic space is seen collapsed onto the floors below. Photo credit: California State Parks, Statewide Museum Collections Center (231-1-489).

Immigrant Records

The administration building burned on August 12, 1940, destroying dormitories, restaurant, offices, and public areas. Fortunately, the Immigration Station’s most valuable records were locked in two steel and concrete vaults or inside filing cabinets rescued from the building. Yet, not all immigration records survived. Many thousands of documents stored in the attic were destroyed.

The most significant losses included hundreds of records relating to Chinese laborers (1887-1905), several series of administrative records, and 35,000 deportation records. Files that survived the fire were safely transferred to other facilities in San Francisco. Several months before the fire, the Works Projects Administration conducted a records inventory at the Angel Island Immigration Station. In their subsequent report, they listed all files held at the site, their locations, and details on their condition. From this report, we can identify which files were lost.

-

• Alien Chinese departure applications, 1904-1912

• Aliens departure register, 1895 to date

• Alien manifests, 1893 to date

• Applications for certificates of identity, 1909-1911

• Arrival and departure certificates for Chinese, 1914 to date

• Arrivals and disposition of alien Chinese, 1903 to date

• Boarding officers’ reports, 1917-1934

• Chinese and Japanese check-out slips, 1913 to date

• Chinese arrivals at Port of San Francisco, 1897-1903

• Chinese departure records and applications for return certificates, 1894-1913

• Chinese manifest and record, 1892-1904

• Chinese mortality list, 1885-1918

• Chinese photographs, 1918 to date

• Crew lists, 1905 to date

• Disposition of aliens, 1928-1931

• Head tax and quota reports, 1912 to date

• Head tax collections, 1901-1909

• Identification cards, 1914-1928

• Identification certificates for Chinese, 1910 to date

• Immigration cases – pending, 1935 to date

• Index of all immigration cases, 1880 to date

• Insular manifests, 1907-1911

• Japanese departure records, 1924-1925

• Miscellaneous records, 1912 to date

• Miscellaneous record books, 1903-1914

• Old records index, 1894-1913

• Passenger lists, 1903-1917

• Passenger lists, Hawaiian Islands, 1902-1907

• Personnel correspondence, 1911 to date

• Pre-examination records, 1929 to date

• Record of aliens held for special inquiry, 1910-1927

• Register of Chinese laborers departing from and returning to the US, 1882 to date

• Special hearings on immigration cases, 1906 to date

• Station log books, 1898-1914

• Stenographers’ notebooks, 1895 to date

• Telegrams relating to immigration cases, 1928-1932

• US citizens’ manifests, 1930 to dateSource: Works Projects Administration. Inventory of Federal Archives, Series XI, Department of Labor, No5 California, June 1940.

-

• Alien head tax refunds, 1919 to date (partial)

• Condensed record of pending cases, 1935 to date

• Correspondence on pending cases, 1936 to date

• Correspondence regarding alien entries, 1935 to date

• Court and bond records, 1912 to date

• Custom House manifests, 1851-1907

• Departure manifests, 1929 to date

• Departures of Orientals, 1932 to date

• Deportation records of Orientals, 1928 to date

• Hospitalization of Orientals, 1928 to date

• Incoming Orientals, 1935 to date

• Index to ship deserters, 1912 to date

• Personal histories of Orientals, 1926 to date

• Personnel records, 1925 to date

• Photo plates and films, 1912-1936

• Refusals for Filipino admittance, 1934 to dateSource: Works Projects Administration. Inventory of Federal Archives, Series XI, Department of Labor, No5 California, June 1940.

-

• Alien certificates issued in insular territories, 1913-1917

• Alien head tax refunds, 1919 to date (partial)

• Alien manifests of China Mail Steamship Co., 1898-1920, 1924-1925

• Alien seamen’s identification cards, 1917-1918

• Arrests and deportations, 1914-1930

• Arrivals and departures of aliens at Angel Island, 1917-1922

• Arrivals of Orientals, 1888-1898

• Bills and fines, 1926-1932

• Cancelled certificates of departing Chinese laborers, 1887-1905

• Certificates of Chinese identity, 1893-1894, 1898-1899, 1904

• Chinese entry cases, 1910-1923

• Chinese, Japanese, and Korean laborers in transit, 1901-1920

• Chinese letters and translations, 1914-1926

• Correspondence on immigration cases, 1911-1932

• Correspondence regarding Chinese immigration, 1904-1912

• Daily night guard reports, 1923-1932

• Daily reports, 1921-1926

• Departures of aliens, 1882-1903

• Deportation warrants, 1929 to date

• Deposit slips and canceled checks, 1911-1914

• Descriptive lists relating to alien laborers

• Detention cards, 1910-1919

• Disbursing officers’ records, 1913-1920

• Discharge of aliens from the hospital, 1924-1930

• Expenditures, 1911-1923

• General correspondence, 1913-1935

• Head tax returns, 1905-1916

• Immigrant accounts, 1911-1923

• Immigrant arrivals, 1907

• Inspectors’ reports on Chinese immigrants, 1907-1911

• Inward passenger list oaths, 1924-1926

• Manifests of incoming and outgoing alien passengers, 1904-1921

• Medical certificates for alien seamen, 1915-1924

• Medical certificates of Chinese arrivals, 1907-1908

• Miscellaneous books, 1898-1918

• Miscellaneous data on Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese

• Miscellaneous letter books, 1883-1912

• Miscellaneous reports and certificates, 1914-1926

• Monthly reports by Commissioner of Immigration, 1922-1926

• Records of hearing and canceled bonds, 1906-1914

• Reports of Commissioner of Immigration to the Commissioner General of Immigration, 1922-1926

• Reports on Chinese arrivals, 1914-1918

• Room assignments, Angel Island, 1910-1913

• Special inquiry identification cards, 1920-1922

• Statement of current accounts, 1912-1920

• Stubs of Chinese labor certificates, 1900-1908Source: Works Projects Administration. Inventory of Federal Archives, Series XI, Department of Labor, No5 California, June 1940.

This digital rendering shows the 1906 floor plan over an aerial view of the Station. The lawn has changed significantly over time and does not retain many of its original features. To scale the floor plan, we used the Tower Room’s egress point and the enclosed porch to align it with the historic hardscape. Photo credit: AIISF

NARA. Acting Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, December 19, 1910.

NARA. Acting Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, February 8, 1911.

NARA. Architect Walter Mathews to Commissioner General of Immigration Frank P. Sargent, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, December 16, 1905.

NARA. Architect Walter Mathews to Commissioner General of Immigration Frank P. Sargent, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, January 4, 1906.

NARA. Architect W.O. Raiguel memorandum, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, February 7, 1911.

NARA. Assistant Surgeon W.W. King to the Surgeon-General of the PHMHS, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, November 12, 1909.

NARA. Commissioner-General to the Commissioner of Immigration, Angel Island, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, December 14, 1912.

NARA. Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, July 19, 1911.

NARA. Commissioner of Immigration, Ellis Island to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, March 27, 1911.

NARA. Commissioner Samuel Backus to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, September 1, 1911.

NARA. Commissioner to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, August 28, 1911.

NARA. Contract for construction of the Immigration Station signed by the Secretary of Commerce and Labor, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, 1906.

NARA. Dr. Melvin Glover, Asst. Surgeon, to the Acting Commissioner of Immigration, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, November 21, 1910.

NARA. Memorandum showing employees quartered and kind of quarters occupied, Record Group 85, General Correspondence, December 14, 1912.

San Francisco Call. “San Francisco to have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World,” August 18, 1907.

San Francisco Call. “San Francisco’s New Ellis Island: How the $500,000 detention station on Angel Island will enable immigration officials to handle the hordes coming across the Pacific and soon to come from Europe through the Panama Canal,” January 19, 1908.

San Francisco Call. “Immigrant Station Pleases Senator: Dillingham Finds Angel Island Buildings Commodious and Well Equipped,” San Francisco Call, October 8, 1909.

San Francisco Call. “Taft Opens Island for Immigrants, Orders Secretary Nagel to Use Money Immediately for Angel Station,” October 10, 1909.

US Public Health and Marine Hospital Service’s “Report of Inspection of Aliens at San Francisco, Cal.,” Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1910.