Journey to America

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, millions of people — in numbers which have not been seen since — came to America in pursuit of a better, freer life. On the east coast, most of the huddled masses were met by the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. On the west coast, between 1910 and 1940, most were met by the wooden buildings of Angel Island.

There, during this period of great migration, they would meet with a reception quite unlike that given to European immigrants on the East Coast. The reasons for this reception, and the story of this journey, as usual, have their roots in the past.

Fifty years beforehand, around the middle of the 19th century, on the far western frontier of the continental United States, immigrants from Guangdong Province in southern China began arriving, fleeing from a land stricken by both natural and man-made disasters and a collapsing rural economy. Though initially welcomed, when the local economy took a downturn in the 1870s, economic problems were laid at the feet of this highly visible minority by organized labor, newspapers, and in short order, politicians.

A number of laws were passed at the local and state levels targeting the Chinese, soon attracting national attention. In order to secure the crucial western states' votes, both parties in Congress supported the first of several acts targeting immigration from Asia. With the passing of this first act, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, America had limited immigration on the basis of nationality or race for the first time, and it would not be the last, as subsequent acts severely curtailed each successive wave of immigration from Asia which came to replace Chinese immigrant workers.

Despite these restrictive laws, immigrants undertook a Pacific Ocean journey of three weeks, including stops in Honolulu, Manila, Yokohama, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Many passengers could barely afford steerage class travel, and bought their tickets only with the collective help of relatives and neighbors. These new immigrants believed that they could make that money back quickly in America. Other immigrants came from the Punjab, Russia, the Philippines, Portugal, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, and Latin America as well. Their stories are not well documented and remain waiting to be uncovered.

Among these immigrants were several hundred Jewish people, fleeing Nazi rule in Germany, Austria, Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

These people had the good fortune to have relatives and sponsors in the US.

After traveling across Russia to China and Japan, they boarded ships for San Francisco. Dozens of families and individuals ended up at the Angel Island Immigration Station, underwent medical inspection and were detained for weeks because they did not have sufficient funds to reach their eventual destinations.

Different Treatment Based on Nationality

On Arrival at San Francisco, passengers would be separated by nationality

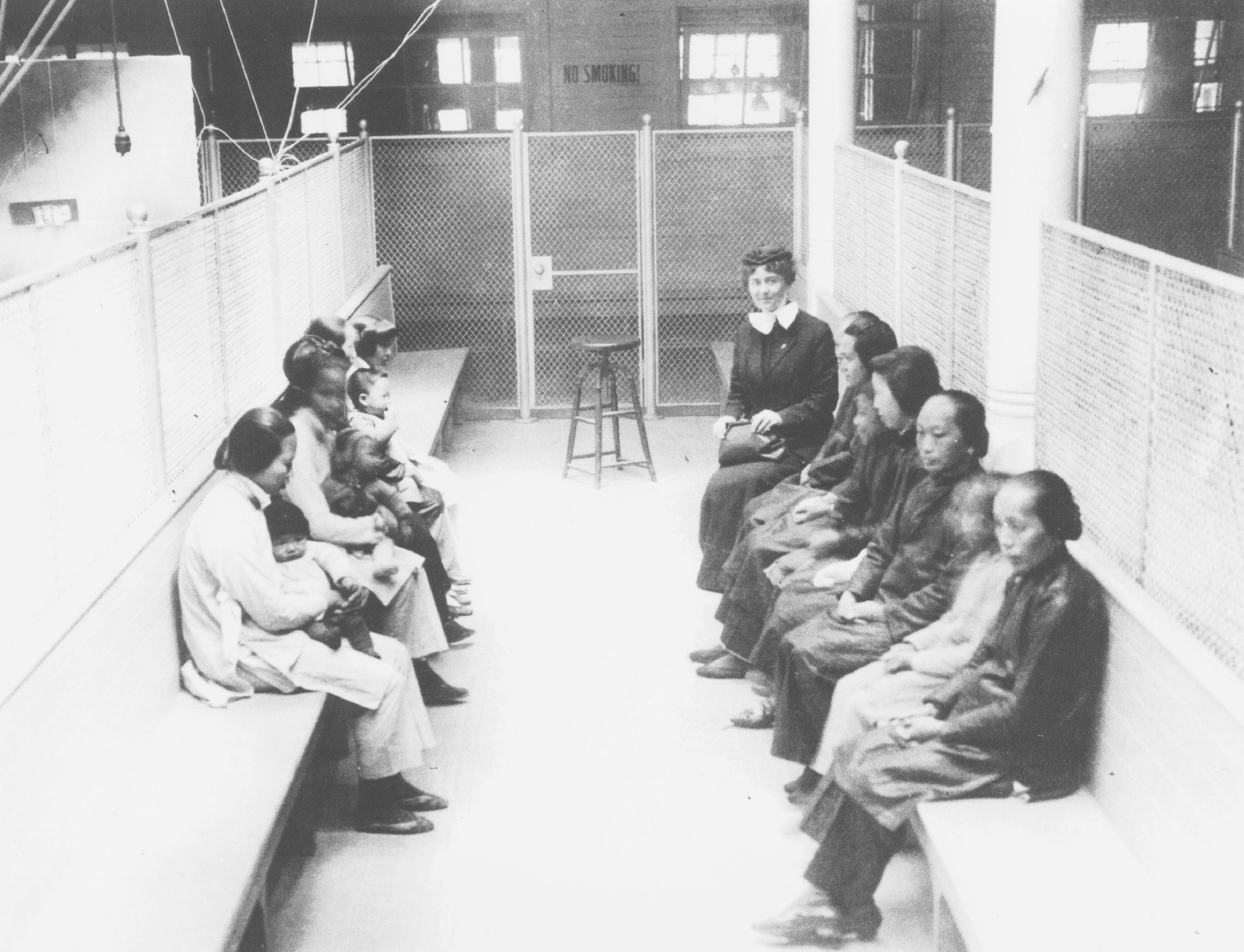

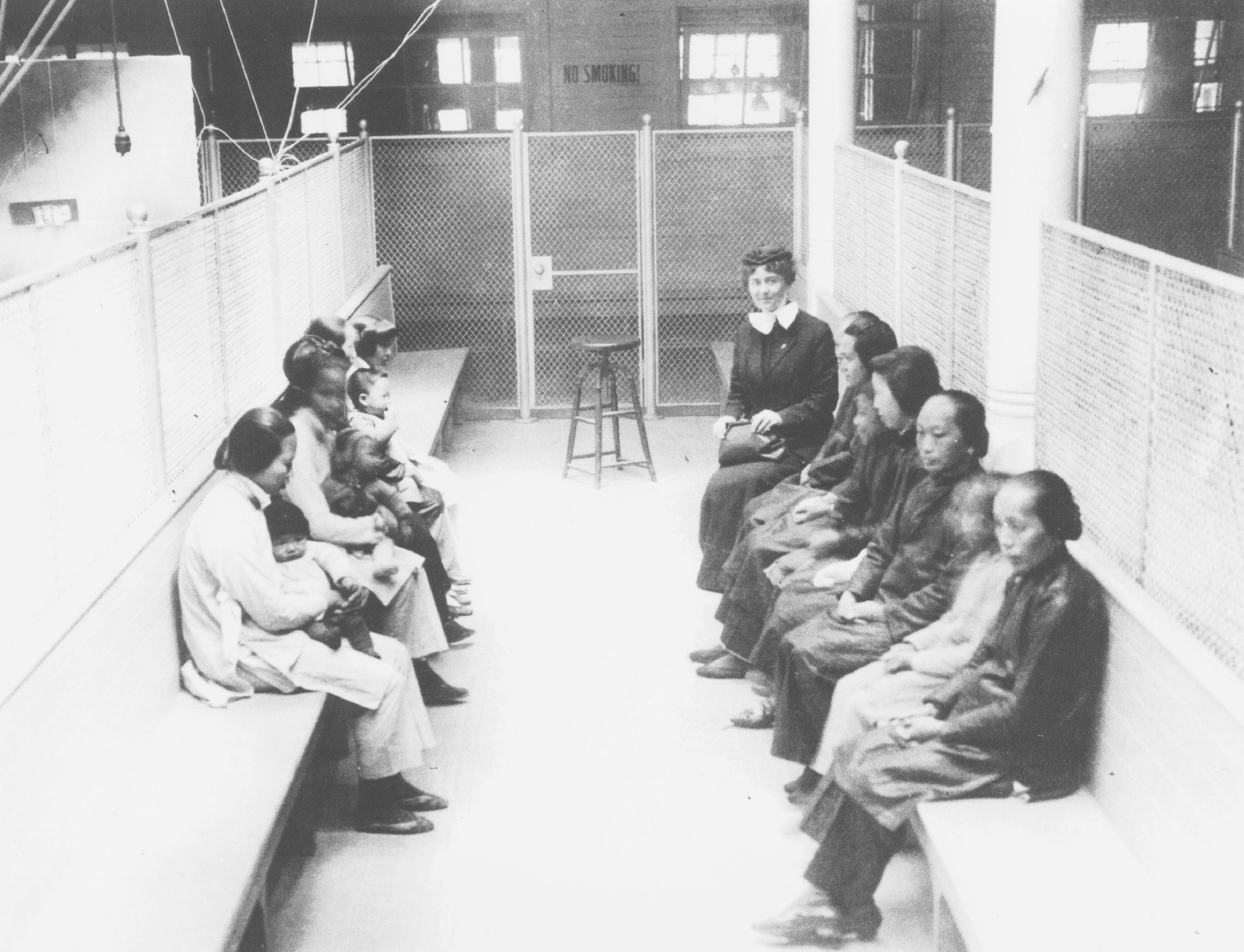

Europeans or travelers holding first or second class tickets would have their papers processed on board the ship and allowed to disembark. Asians and other immigrants, including Russians, Mexicans, and others, as well as those who needed to be quarantined for health reasons, would be ferried to Angel Island for processing.

Enforcement

The question soon arose of how to actually implement the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Initially, customs service officers individually and arbitrarily administered Exclusion; in time, procedures became standardized and as they did, Exclusion enforcement eventually fell upon the Bureau of Immigration, forerunner of today's Bureau of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), formerly Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). By the first decade of the 20th century, a national system had formed for specifically regulating Asian immigration. This system invoked fear and loathing in the community, and remained a baleful memory for generations.

As part of this system, Immigration officials planned a new facility on Angel Island, the largest island in the San Francisco Bay, far from the mainland. It would replace the old two-story shed at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company wharf previously used to house and process incoming and outgoing migrants. The new station would prevent Chinese immigrants from communicating with those in San Francisco, isolate immigrants with communicable diseases, and, like the prison on nearby Alcatraz Island, be escape proof. In January 1910, over the late objections of Chinese community leaders, this hastily built immigration station was opened on the northeastern edge of Angel Island, ready to receive its first guests.

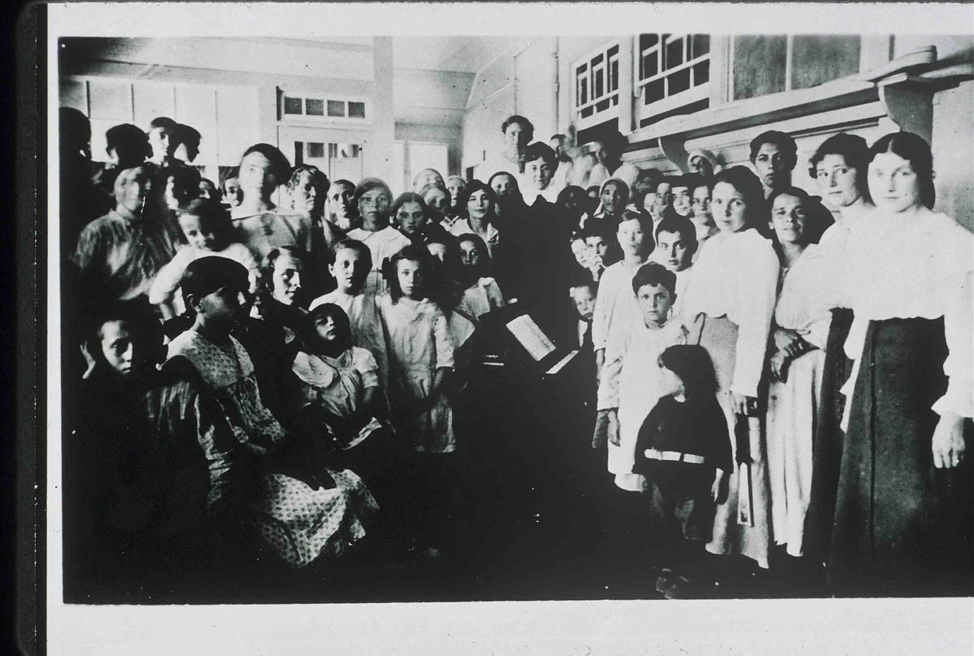

The first stop on disembarking at the pier on Angel Island was the Administration Building. Men were separated from women and children, then proceeded for medical exams, a humiliating experience for Asians, whose medical practice does not include disrobing before the leering eyes of strangers or being probed and measured by metal calipers. Here, they would also be tested for parasitic infections. Consequences could be severe for failing this test, including hospitalization at their own expense or deportation. After the examinations they were then assigned a detention dormitory and a bunk, where they would await their interrogators, the Board of Special Inquiry.

Circumventing the Chinese Exclusion Act became a first order concern for most immigrants from China, as it allowed only merchants, clergy, diplomats, teachers, students as “exempt” classes to come here. Many Chinese immigrants resorted to buying false identities at great cost, which allowed them to immigrate as either children of exempt classes or children of natives. In 1906, the San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed municipal records which created an opportunity for the city’s Chinese residents to claim that they were born here and therefore were American citizens. As citizens Chinese could bring their children to this country, and on return visits to their ancestral villages, claim new children had been born to them. Some of these were “paper sons” or less frequently “paper daughters” — children on paper only without a direct family connection.* These paper children were in effect “slots” which people could sell to allow new immigrants to come to this country.

To counter this practice, Immigration inspectors developed grueling interrogations, and by 1910 they had refined this procedure.

The immigrant applicant would be called before a Board of Special Inquiry, composed of two immigrant inspectors, a stenographer, and a translator, when needed. Over the course of several hours or even days, the applicant would be asked about minute details only a genuine applicant would know about — their family history, location of the village, their homes. These questions had been anticipated and thus, irrespective of the true nature of the relationship to their sponsor, the applicant had prepared months in advance by committing these details to memory. Their witnesses — other family members living in the United States — would be called forward to corroborate these answers. Any deviation from the testimony would prolong questioning or throw the entire case into doubt and put the applicant at risk of deportation, and possibly everyone else in the family connected to the applicant as well. These details had to be remembered for life. Because of return trips to China, the risk of random immigration raids and identity card checks on the street, a paper son often had to keep these details alive throughout their life.

In the meantime, immigrants suffered through long waits on Angel Island for these accounts to be taken or to arrive in a world before instantaneous electronic communication. This period could range from several weeks if the testimony was taken locally to several months to years if the applicant was rejected and appealed the decision. The length of stay varied for travelers from other countries; Japanese immigrants held documents provided by their government that sometimes expedited the process of entering the country, and thus, the majority of the detainees were Chinese. Often, one’s relatives might be on the other side of the country in New York or Chicago. Wherever they were, until their testimony was taken and corroborated and found its way back to San Francisco, the applicant would languish in detention.

Down In Flames

Down in Flames

In the end, the complaints of the community and public officials regarding the safety of the Immigration Station proved true when the Administration Building burned to the ground in August 1940. All applicants were relocated to a mainland facility by November. In 1943, Congress finally repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in consideration of its ally in the Pacific Theater, thus ending 61 years of official Exclusion. But there was a twist: while the repeal finally allowed Chinese to become naturalized citizens at last, it continued to limit immigration from China to a mere 105 people a year until 1965.*

Once closed due to fire, the Immigration Station site was used as a World War II prisoner of war processing center by the U.S. military. After the war, the site was abandoned and deteriorated. In 1963, Angel Island was established as a state park and the California Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) assumed stewardship of the immigration site.

Japanese American Detainees on Angel Island in World War II

Japanese Internment

The story of Angel Island as a center for processing U.S. immigrants did not end when the Administration Building burned down in an electrical fire in 1940. Almost 700 Japanese immigrants were sent from Hawaii to the mainland after Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japan on December 7, 1941. Close to 600 of these people were first detained in the former immigration barracks on Angel Island, with the other 105 being sent to Sharp Park, near Pacifica. In addition, at least 98 mainland Japanese immigrants were arrested and brought to Angel Island. Most of them came from the Bay Area, Central and Salinas Valleys, with some from Colorado and Washington.

For some, Sharp Park was their first site for further screening - those deemed the most "dangerous" were sent to the U.S. Army camp on Angel Island (Fort McDowell) and then to Army and Department of Justice camps, while others were allowed to join their families at the War Relocation Authority camps like Poston, Arizona, Jerome, Arkansas, and Tule Lake, California. They were considered internees under the control of the U.S. government, both the U.S. Army and the Department of Justice.

Restoration of an Immigration Landmark

In time, Angel Island began to recede into memory like fog in the bay. The traumatic experiences that Asian communities and other groups immigrating over the Pacific had faced there were rarely if ever mentioned to future generations. In 1970, shortly before the scheduled destruction of the barracks, a California State Park Ranger, Alexander Weiss, rediscovered the poetry on the walls of the abandoned barracks.

Ranger Weiss contacted Professor George Araki of San Francisco State College and photographer Mak Takahashi; together they photographed the walls of the barracks. Sparked by the discovery, Bay Area Asian Americans, spearheaded by Chris Chow, formed the Angel Island Immigration Station Historical Advisory Committee (AIISHAC). This organization studied how best to preserve the station for historical interpretation.

Restoring the Barracks

In July 1976, their hard work came to fruition as the state legislature appropriated $250,000 to restore and preserve the barracks as a state monument. In 1983, the barracks opened to the public and members of AIISHAC created the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF) to continue preservation and educational efforts regarding the site. AIISF is the non-profit partner of California State Parks in the work to restore the historic immigration station at Angel Island. AIISF’s mission includes both the preservation of the site and education about the role of Pacific immigration in U.S. history.

In 1997, the Angel Island Immigration Station was declared a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service. In 1999, Save America’s Treasures, a project of the National Trust and the White House Millennium Council, adopted Angel Island Immigration Station as one of its Official Projects, providing $500,000 for the preservation of the precious Chinese poems carved into the barracks walls. In March 2000, California voters passed a state bond measure that set aside $15 million specifically for restoration of the Angel Island Immigration Station.

In 2004, the Immigration Station was closed for a major retrofitting and renovation work. Over the next five years, many changes were made to the detention barracks: a new roof was installed, an elevator and wheelchair lift were added, new exhibits were created to highlight the significance of the Chinese poetry carved on the walls, and exhibits such as the interrogation table and other interpretive signs were placed on the grounds of the old administration building.

In February 2009, the immigration station reopened. In 2010 work began to stabilize the immigration station hospital, a two-story, and 10,000 square foot structure, directly across from the detention barracks. The hospital played an important role at the immigration station as the site of inspection, quarantine, and healing of immigrants.

The first phase of the hospital project is the stabilization of the structure, which has suffered significant water damage and structural weakening. By spring 2012, a new roof and gutters had been installed at the hospital, and the interior walls had been strengthened. The final phase of rehabilitation of the hospital began in fall 2013 and lasted until 2020. It reopened in 2022 as the Angel Island Immigration Museum (AIIM). AIIM will tell the stories of the struggles and successes faced today and in the past, and of the powerful legacy of America’s immigrants- bringing voice to the West Coast immigration experience. Performance, cultural and community-building events, and symposia -- in addition to the exhibits -- will raise the profile of the West Coast immigration experience and ensure that it becomes a part of our nation’s immigration history narrative.

The Angel Island Immigration Station continues to be a part of America’s story. The Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation works to bring its history to light and to make its lessons part of our national dialogue about the complicated intersection of race, immigration and the American identity.

California State Parks and the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation wish to thank the following contributors whose generosity made possible the completion of Phase One of the restoration of the U.S. Immigration Station, Angel Island

A Save America's Treasures federal grant, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior; Save America's Treasures at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, including major support from: The Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, Marin Community Foundation, The J. Paul Getty Trust's Preservation Planning Fund, and Ms. Yeni Wong; The National Trust for Historic Preservation through: American Express Partners in Preservation program, in partnership with the American Express Foundation, The Cynthia Woods Mitchell Fund for Historic Interiors, and The Johanna Favrot Fund for Historic Preservation; California Cultural and Historical Endowment; California Parks Bond Act of 2000, Gee Family Foundation, Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, Walter and Elise Haas Fund, and J.T. Tai & Company Foundation.

Additional Funders

Thomas & Eva Fong Family Foundation, Ken Lee Family Foundation, Lawrence Choy Lowe Memorial Fund, and Look Lowe Family Trust.

With special appreciation to the following

Angel Island Immigration Station Historical Advisory Committee, Architectural Resources Group, California State Parks Foundation, California State Senator John Burton, Donald Bybee, Chris Chow, Paul Chow, Phillip Choy, Ruth Coleman, Charles Egan, Erika Gee, Nicholas Franco, Forrest Gok, Elizabeth Goldstein, Dave Gould, Tod Hara, Daniel Iacofano, Kathy Lim Ko, Kimball Koch, Daphne Kwok, Him Mark Lai, Erika Lee, Newton Liu, Wan Liu, Felicia Lowe, David Matthews, Dale Minami, Ray Murray, Brian O'Neill, National Archives-San Francisco, Francelle Phillips, Daniel Quan Design, Danita Rodriguez, Douglas Tom, Katherine Toy, Kathy Owyang Turner, Xing Chu Wang, Connie Yung Yu, and Judy Yung.