Vault #22: Prisoners of War

A Timeline of the Post-Immigration Era (1941 to 1946)

The US government built a mess hall beside the detention barracks for German and Japanese prisoners of war. It is one of the few remaining World War II-era structures at the site. AIISF.

For decades, Angel Island was a gateway for immigrants arriving in the US. But from 1942 to 1946, the island took on a starkly different role. The former immigration station was transformed into North Garrison, Fort McDowell—a military detention center where Japanese, German, and Italian prisoners of war were held alongside Japanese Americans detained by the US government.

Though this chapter of Angel Island’s past is less well known, the stories of those who lived through it remain, quite literally, written on the walls. Inscriptions left behind by prisoners—carved in frustration, fear, or simply to mark their existence—serve as reminders of their experiences. Through historical records, photographs, and firsthand accounts, this timeline brings their stories to light, ensuring that this chapter of Angel Island’s history is not lost to time.

1941: War Comes to the US

Room 203 of the barracks was used as a guard room during World War II, 2024. AIISF.

Opening the Camp

DECEMBER 7, 1941: Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, a prisoner of war processing camp opened at the former Immigration Station. The site was renamed North Garrison, Fort McDowell.

Photo: Site plan for the North Garrison, 1941. Buildings numbered in the 300s were built in 1908. Buildings numbered in the 200s were built after the Immigration Station closed. NARA.

1942: The First Prisoners

A photo of Ensign Sakamaki’s submarine (HA-19) beached on Oahu on December 8, 1941 (cropped from the original). Naval History and Heritage Command and NARA.

Transferred from Hawai'i

MARCH 1, 1942: Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, captain of a one-man submarine at Pearl Harbor, was the first Japanese prisoner of war captured by the United States. Sakamaki arrived at Angel Island on March 1st with 172 Japanese American men arrested after the US entered the war.

To learn more about the experiences of Japanese Americans on Angel Island during World War II, visit our exhibit, Taken From Their Families.

Photos: (left) Sakamaki dressed in his uniform; (right) Sakamaki photographed as a POW. His face shows self-inflicted burns from a cigarette.

Captured at Sea

JULY 1942: The first group of Japanese prisoners—five officers and thirty-five men—began their detention on Angel Island. Over the next few months, Japanese men captured in the Pacific War were briefly held in the barracks. They participated in the following battles against the US:

• Battle of Coral Sea

• Battle of Midway

• Battle of the Eastern Solomons

Photo: Japanese prisoners of war under guard on Midway, following their rescue from a lifeboat, 1942. Naval History and Heritage Command and NARA.

1943: German Prisoners of War

The word “stubendienst” appears on the wall of room 207. It’s a German term used to describe room duty prisoners. It is one of very few German POW inscriptions in the building. AIISF.

Afrika Korps

JUNE 9, 1943: Following the Tunisian Campaign in North Africa, Lieutenant General Karl Bülowius, three German generals, a colonel, and a major were imprisoned on the island.

The San Pedro News Pilot reported Austrian, Pole, and Czechoslovakian conscripts were among the Afrika Korps prisoners. They were segregated from the German soldiers.

Fox Movietone captured footage of the men inside the barracks and mess hall. Roger A. Johnson with the Los Angeles Times also described their detainment:

“During the early spring months some of the prisoners arrived at foggy San Francisco Bay wearing desert short pants direct from the sands of Egypt…

The camp’s daily schedule is fixed. Reveille is at 6 am, breakfast at 6:30. From 7:30 to 9 am they clean their own quarters. From 9 to 11 am they take their exercise—walk around the island under escort, mow the lawn, or rake leaves... Lunch is from noon to 1 pm. They rest from 1 to 2 pm, exercise again from 2 to 4, and eat supper at 5 pm…

They work in a Victory garden which is handed on from one batch of prisoners to the next. The one arriving in July and August will reap the harvest of Japanese and Germans who did the planting in March and April.”

Photo: An Axis prisoner of war with a GI meal on Angel Island, 1943. US Air Force and NARA. (cropped from the original)

Italy Surrenders

SEPTEMBER 8, 1943: There were Italian Service Units (ISUs) on Angel Island when Italy surrendered to the Allies in World War II. They were not under constant confinement on Angel Island like German and Japanese prisoners of war. They worked as groundskeepers and gardeners at Fort McDowell. Unlike other prisoners, they were allowed to attend dances and parties in San Francisco and entertain visitors on the island.

After the war ended, a female US Marine flew to Rome to marry Aldo Ferraresi—an Italian prisoner she met on Angel Island.

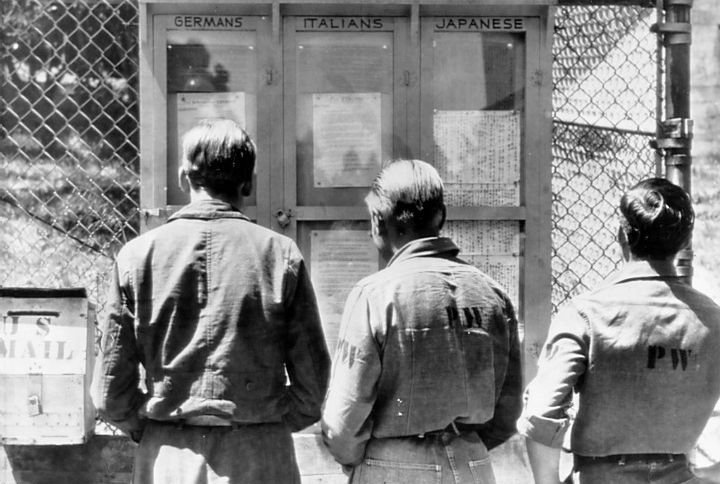

Photo: Prisoners of war stand in front of a bulletin board at the North Garrison. Notices in German, Italian, and Japanese can be seen, 1943 (cropped from the original). US Air Force and NARA.

1944: The War Continues

The 1929 Geneva Convention was an international treaty that ensured prisoners of war would receive compassionate and humane treatment during wartime. To abide by this agreement, room 204 was transformed into infirmary for prisoners. A US Army doctor held daily sick calls, treating an estimated 140 prisoners per week. AIISF.

Korean Conscripts

MARCH 1944: A Japanese prisoner, Hajime Ōtsuka, was held on Angel Island. An inscription in room 209 warns of his arrival.

Dangerous person

Coming from Saipan.

Ōtsuka [??]

Beware!!

MAY 18, 1944: There were 528 Japanese prisoners in barracks, leaving only twelve beds available. A report filed on this date mentioned several Koreans were segregated from Japanese prisoners.

Photo: A pencil inscription warning about Ōtsuka, scratched over (room 209). AIISF.

Translation: Egan, Charles. Voices of Angel Island: Inscriptions and Immigrant Poetry, 1910-1945. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Island to Island

SEPTEMBER 10, 1944: 42 Japanese prisoners arrived on the island. One individual left an inscription in an upstairs sitting room (room 209).

On September 10, 1944, came to this island from Hawai'i.

42 [?] persons.

SEPTEMBER 12, 1944: A Japanese prisoner of war leaves his mark in room 109.

We arrived here on September 12.

We did not find our place of death—

We were captured and are detained here.

SEPTEMBER 13, 1944: 450 Japanese prisoners who were captured overseas arrive on Angel Island. They fought in several Pacific battles:

• Battle of Buna-Gona

• Battle of Attu

• Battle of Saipan

• Battle of Guam

• Battle of Tinian

Photo: A character drawing made by a prisoner of war, located in room 209. AIISF.

Translations: Egan, Charles. Voices of Angel Island: Inscriptions and Immigrant Poetry, 1910-1945. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Early 1945: The Last Prisoners

A prisoner of war inscription in room 115 says, “Long live the Great Japanese Empire!” AIISF.

Germany Surrenders

FEBRUARY 24, 1945: A visit report shows that only four Japanese prisoners were being held at the North Garrison. They served as first and second lieutenants of the Japanese army’s medical corps.

MAY 8, 1945: When Germany surrendered, 277 German prisoners were on Angel Island.

Photo: An inscription from a German prisoner says, “Türe zu wegen Durchzug” or “Close the door. There’s a draft.” AIISF.

Child Soldiers

JULY 2, 1945: A visit report recorded 254 Japanese prisoners on the island. Of that number, 15 were officers. The report also called out an 11-year-old soldier nicknamed “Peanuts,” whom they say is a “favorite.” The prisoners were captured while fighting in the following campaigns and battles:

• Battle of Peleiu

• Philippines Campaign

• Battle of Iwo Jima

• Battle of Okinawa

AUGUST 9, 1945: The SF News reported on Japanese prisoners at the site. One of the US Army translators photographed for the article, Private First Class Peter Ota, remembered seeing child soldiers from the Battle of Okinawa arriving on Angel Island.

“We were shocked. They were kids. They looked like kids who were lost.”

Japanese prisoner Mitsugu Sakihara was a fourth-year student at Naha Commercial Middle School before he was called to serve in the Iron and Blood Loyalist Troop. In his published story, Sparrows of Angel Island, he recalled his time as a POW.

“The barracks were filled with the bright morning sun. I’d been awake for a while but stayed in bed simply because the white linen sheets felt so clean and pleasant… Except for the wire fence around the compound and watchtowers on the corners, American POW camps were not at all like the prison I had been expecting or fearing.”

Photos: (top) A typical mid-day meal in the mess hall; (bottom) Japanese American soldiers in the US Army serving as interpreters at the camp, L to R, Corporal Saburo Hirose, Private Tom Shimiza, Private George Inoye, Pfc. Saburo Hara, and Pfc. Pete Ota, August 9, 1945. The S.F. News.

Late 1945: Repatriation Effort

Child soldier, Mitsugu Sakihara, remembered his first meal on the island in 1945. “The mess hall was simple but very clean. Inside, we picked up a tray and stepped up to a counter where a big Caucasian slapped food onto our tray as we passed by. We served ourselves toast and milk or coffee and sat wherever we wanted.” Photo of the mess hall counter, 2025. AIISF.

Japan Surrenders

SEPTEMBER 2, 1945: Japan surrendered to the Allies in World War II, leading to a prisoner repatriation effort by the US government.

SEPTEMBER 7, 1945: 241 Japanese prisoners captured at the Battle of Okinawa were ordered back to Angel Island.

SEPTEMBER 25, 1945: The first of three ships repatriating Japanese nationals left San Francisco. An estimated 300-500 people are aboard.

OCTOBER 1945: Another ship of repatriates left. Their numbers were not reported.

Photo: Japanese prisoners line up behind the barracks, August 15, 1945. OpenSFHistory / wnp27.7688.

Returning Home

NOVEMBER 7, 1945: Nearly 700 Japanese prisoners of war left San Francisco aboard the USS Sea Flasher. Their numbers included 100 hospital patients, 3 officers, 401 enlisted men, and 271 civilians working with the Japanese Army and Navy. They boarded the ship with twelve urns containing the remains of fellow soldiers who died in the US.

Photo: The inscription is one of ten Japanese inscriptions mentioning the November 7th departure (room 115).

The time has come for me to fulfill my duty.

I think that until it becomes clear whether or not

The separation of life and death will come between us,

I will hold strongly to the proper course.

I pray you will make strong efforts.

More than 600 persons are leaving on November 7.

Translation: Egan, Charles. Voices of Angel Island: Inscriptions and Immigrant Poetry, 1910-1945. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

1946: Closing the Camp

One guard tower used during World War II still stands 80 years after the site closed as a prisoner of war camp, 2025. AIISF.

The Final Departure

JANUARY 8, 1946: The last Japanese national was repatriated. The building and site becomes surplus government property a short time later.

Photo: An inscription on the door to room 207 reads, “19 + K + M + B + 46,” which is a reference to the Christian holiday of Epiphany (January 6th). It is last dated inscription made by an immigrant or prisoner in the building. Two days later, the last Japanese POW left Angel Island. AIISF.

AIISF would like to acknowledge Dr. Charles Egan for his tireless work translating prisoner of war inscriptions and Larisa Proulx for her dedicated research into World War II imprisonment on Angel Island, which made this Vault post possible. By preserving and sharing these histories, we ensure that the stories of those confined within the barracks’ walls are not forgotten.

Bath, David W. "The Captive Samurai: Japanese Prisoners Detained in the United States During World War II,"" University of North Dakota, 1992.

Egan, Charles. Voices of Angel Island: Inscriptions and Immigrant Poetry, 1910-1945. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Krammer, Arnold. "Japanese Prisoners of War in America," Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 52, No. 1, February 1983.

Los Angeles Times. "Nazi Prisoners Like War Camp in United States," June 10, 1943.

NARA. Correspondence from the Brigadier General of the G.S.C. to the Assistant Chief of Supply, War Department, October 22, 1942.

NARA. Correspondence from the Brigadier General of the Aliens Division to the Construction Branch, SOS, War Department, January 5, 1943.

NARA. Report of Visit to POW Base Camp, Angel Island, California, May 2, 1944.

NARA. Report of Visit to POW Basse Camp, Angel Island, California by the International Committee of the Red Cross, September 16, 1944.

NARA. Correspondence from Captain John Witlock to the Provost Marshal General, September 29, 1944.

NARA. Report of Visit to Japanee Prisoner of War Camp, Angel Island, California, July 2, 1945.

Oakland Tribune. "Captives Happy on Angel Isle," June 13, 1943.

Oakland Tribune. "Italian Prisoners Held at Angel Island," June 14, 1943.

Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation. "Cultural Landscape Report for the Angel Island Immigration Station," vol. 1, 2, and 3. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2002.

Rock, Adam. "The American Way: The Influence of Race on the Treatment of Prisoners of War During World War Two," University of Central Florida, 2014.

Sakihara, Mitsugu. "Sparrows of Angel Island: The Experiene of a Young Japanese Prisoner of War," Manoa, Vol. 8, No. 1, University of Hawai'i Press, 1996.

San Pedro News Pilot. "Nazi Prisoners in S.F. Bay Camp Lead Life of Leisure," June 14, 1943.

The S.F. News. "No Coddling for Jap PWs on Angel Island," August 9, 1945.