Vault #15: Employee Cottages

The Faces, Families, and Homes on the Other Side of the Fence

Although the historic homes of the Immigration Station no longer exist, visitors can discover their remnants across the 14.3-acre site. You can access this Google Map from your phone on your next trip to find their location. Click on the map’s icons and shaded areas to see additional photos and learn more about the site.

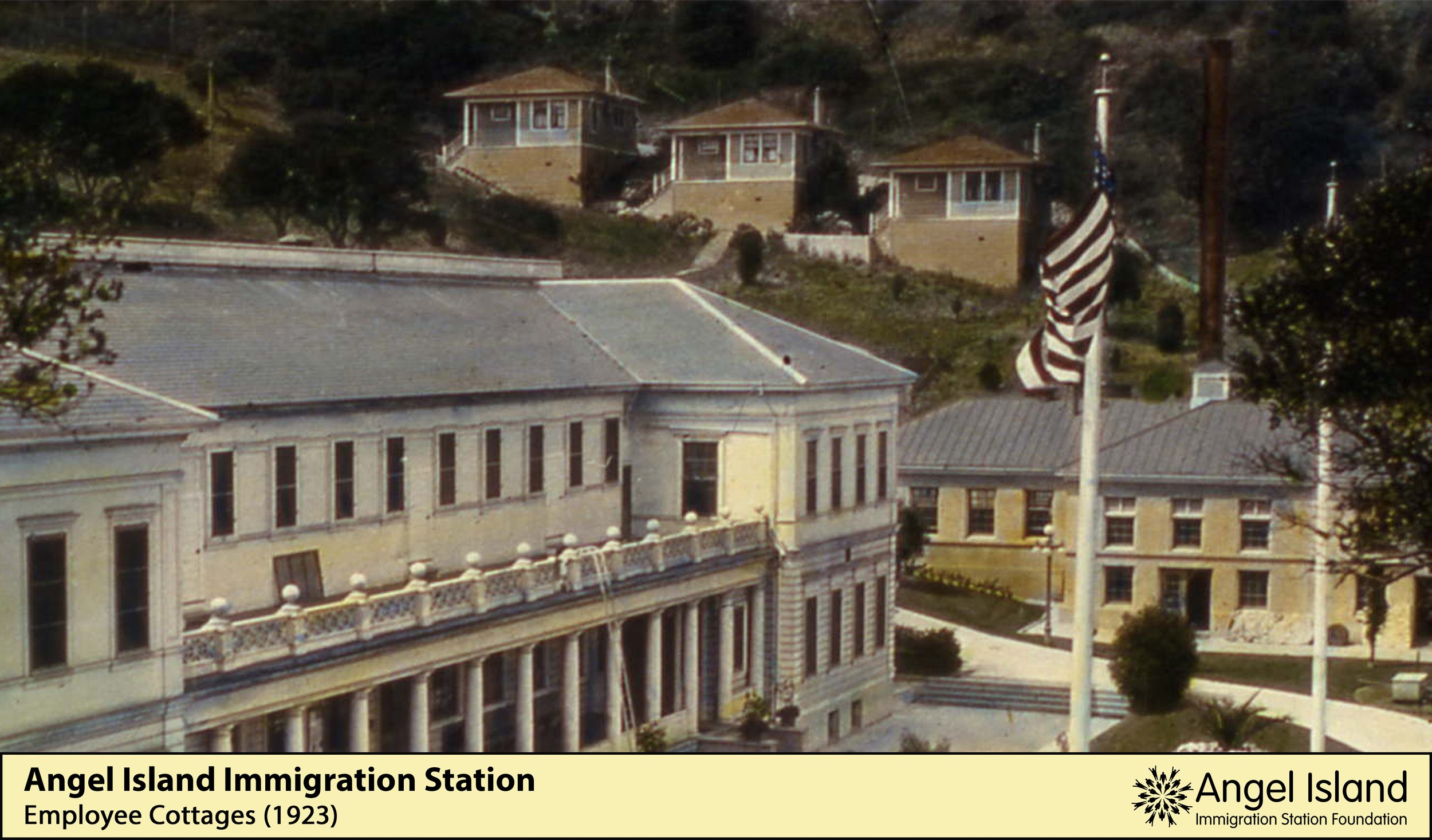

The employee cottages were built on Angel Island in late 1910. Eleven of the twelve cottages can be seen in the photo, with the detention barracks situated between them. Photo: OpenSFHistory/wnp14.10845.

Workers and Accommodations

Working and living on Angel Island during the Immigration Station's operation presented unique opportunities and challenges for the employees. On-site housing provided a level of convenience, allowing staff members to be on hand at all times. However, it meant being isolated from the resources and amenities of San Francisco.

Despite the beautiful surroundings, the island’s remote location posed logistical challenges for kids attending school, shopping for food and supplies, and staying connected with the outside world. For employees who raised a family on a site primarily known for detaining immigrants, balancing work responsibilities with home life required resilience and adaptability.

Employees who lived at the site had critical roles in maintaining the Station’s equipment/infrastructure, prepping meals, or supervising immigrant detainees. Nurses, hospital attendants, cooks, servers, matrons, watchmen, and engineers worked outside regular business hours and needed to be available in an emergency. Realizing the critical nature of their responsibilities, the Bureau of Immigration ordered twelve bungalow cottages to be constructed for these employees and their families.

Julia Morgan on Angel Island

Julia Morgan is most well-known for designing Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California. She was hired in 1919 to design the main building. Miss Morgan continued supervising every aspect of the castle’s construction for the next 28 years.

Towards the end of 1909, the Immigration Station tried to hire an architect for the twelve cottages, but the architect they chose declined. The bureau’s second choice, famed architect Julia Morgan, was soon selected for the project. Immigration Commissioner Hart Hyatt North personally recommended Morgan in his December 1909 memo to the Commissioner General.

“Mr. Howell was unable to find time during his limited stay here to prepare the plans for the necessary quarters for employees. Authority is therefore requested to engage the firm of Morgan & Hoover, architects of this city, at a compensation not exceeding five percent of the gross outlay, to prepare the necessary plans and specifications, etc.”

Unknown to the Commissioner General, Julia Morgan was the sister to Commissioner North’s wife. Her connection to North undoubtedly gave her an advantage in bidding for the contract. Morgan completed her plans for the three- and four-room cottages by May 1910. She also completed drawings for the hospital’s disinfecting room around this time.

In October 1910, Morgan changed the front steps and porches for cottages 1, 11, and 12 to better suit the site conditions. She also reversed the floor plans of the three cottages above the power house to increase sun exposure in the living rooms.

Although Julia Morgan was hired with her partner Ira Hoover under Morgan & Hoover (1907-1910), she completed the cottage designs under her private practice. Photo credit: UC Berkeley, Environmental Design Archives.

Morgan originally designed the cottages without full bathroom facilities to save on construction costs. Commissioner Luther Steward found this decision unacceptable and requested additional funds to correct the oversight. In her revised designs, dated June and November 1910, she showed the bathroom addition extending from the rear of each cottage about two feet.

After Hart Hyatt North stepped down as immigration commissioner, Special Agent Clayton Herington investigated the nepotistic appointment of Morgan & Hoover and found “the only suspicious circumstances was the fact that Commissioner North did not disclose his relationship with Miss Julia Morgan.”

Changing the Landscape

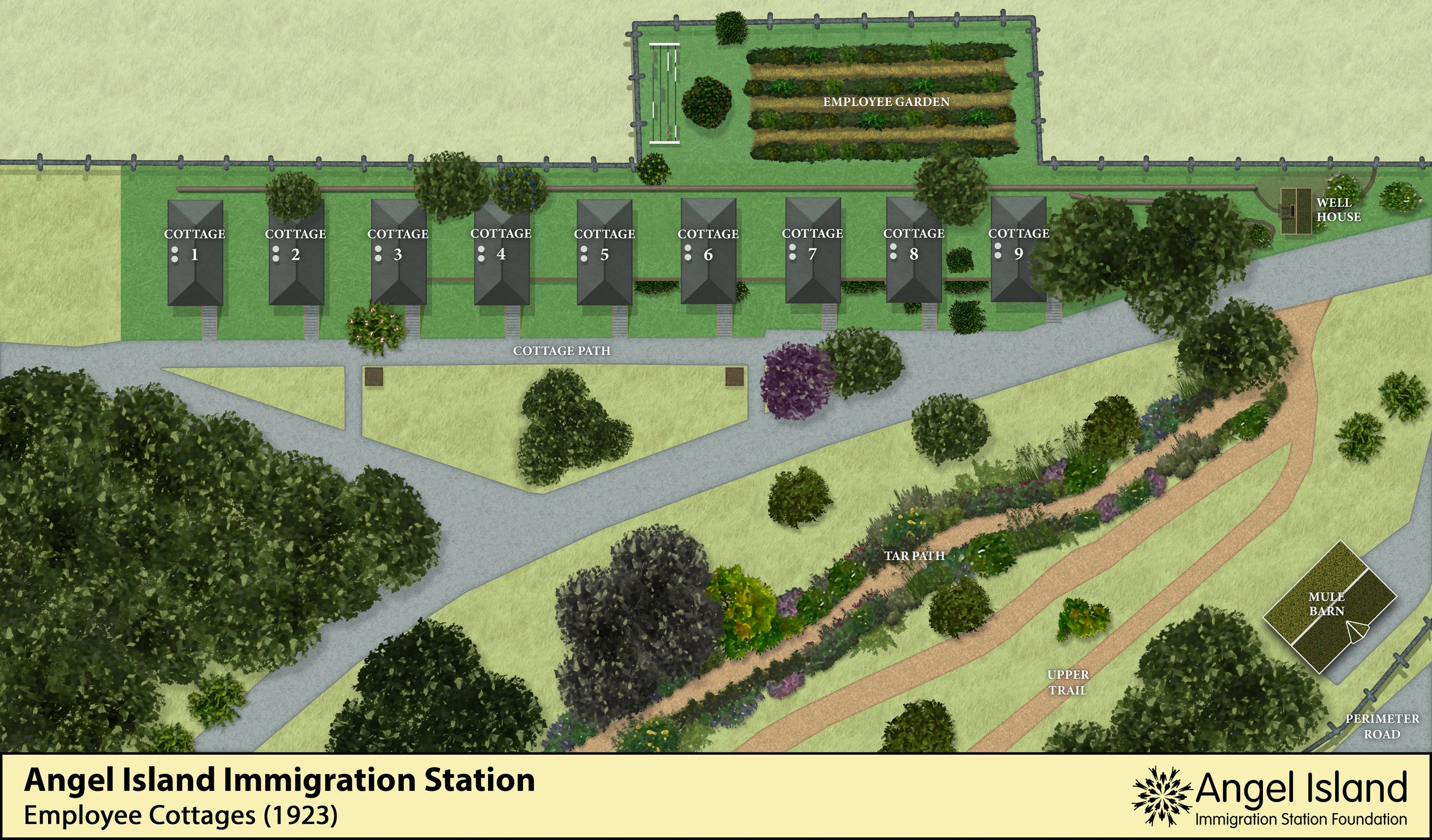

Cottages 1-9

The most suitable location for nine employee cottages was a gently sloped area on the eastern border of the Immigration Station. However, the land was occupied by the US Army. Commissioner North sent a letter to Washington explaining a misunderstanding when the site’s original boundary lines were surveyed. In response to North’s letter, an additional 4.2 acres was given to the Bureau of Immigration.

“When this site was picked out, it was my understanding that the easterly line was several hundred feet further in that direction… I think it was so intended, but the surveyor misunderstood my instructions, as he came to me in the first place to get his general bearings. The line as at present is within six feet of the easterly side of the hospital building. Just beyond that is a ridge beautifully situated and having considerable flat ground upon which dwellings could be erected.”

The space adjacent to the cottages was used for ornamental gardens, and the open area below the cottages was planted with a few trees. Residents decorated their houses with Christmas berry (toyon) branches during the holidays, which prompted Commissioner Haff to issue the following advisory in November 1932.

“All trees and shrubbery, including toyons, that are growing outside the premises allotted to the occupants of the cottages at this station are government property; and therefore, no employees will be permitted to take any berries therefore, nor cut or break any of the branches, without permission of this office.”

Employee Gardens

After the cottages were completed and residents had moved in, there were immediate complaints about the army’s horse corral, which smelled of manure and attracted flies to cottages 6, 7, 8, and 9. The army remedied the residents’ complaints by giving the Immigration Station an additional 50 by 120 ft. plot in 1916. Fourteen years later, the army retook the land unexpectedly, prompting Commissioner John Nagle to send a sternly worded letter to Washington.

“This ground was fenced in and was utilized principally for drying clothes and for gardens, the space between the cottages not being sufficient for these purposes… As a matter of fact, this ground when fenced in serves an additional purpose because it keeps horses outside the corral away from the cottages, thus avoiding to a certain degree extent odors and other incidental nuisances. The undersigned takes this occasion to refer generally antagonistic and non-cooperative attitude of the present commanding officer at Fort McDowell.”

A group of engineers stand outside the power house with the Station’s laborer/driver (far left, Cottage 10) and gardener, Joseph Silva (far right, Cottage 6). Several residents of the island include Henry Niemann (second from left, Cottage 8), Albert Thau (fourth from left, Cottage 9), and Alonzo Peery (fourth from right, Cottage 7). Photo credit: California State Parks, Statewide Museum Collections Center (231-20-23).

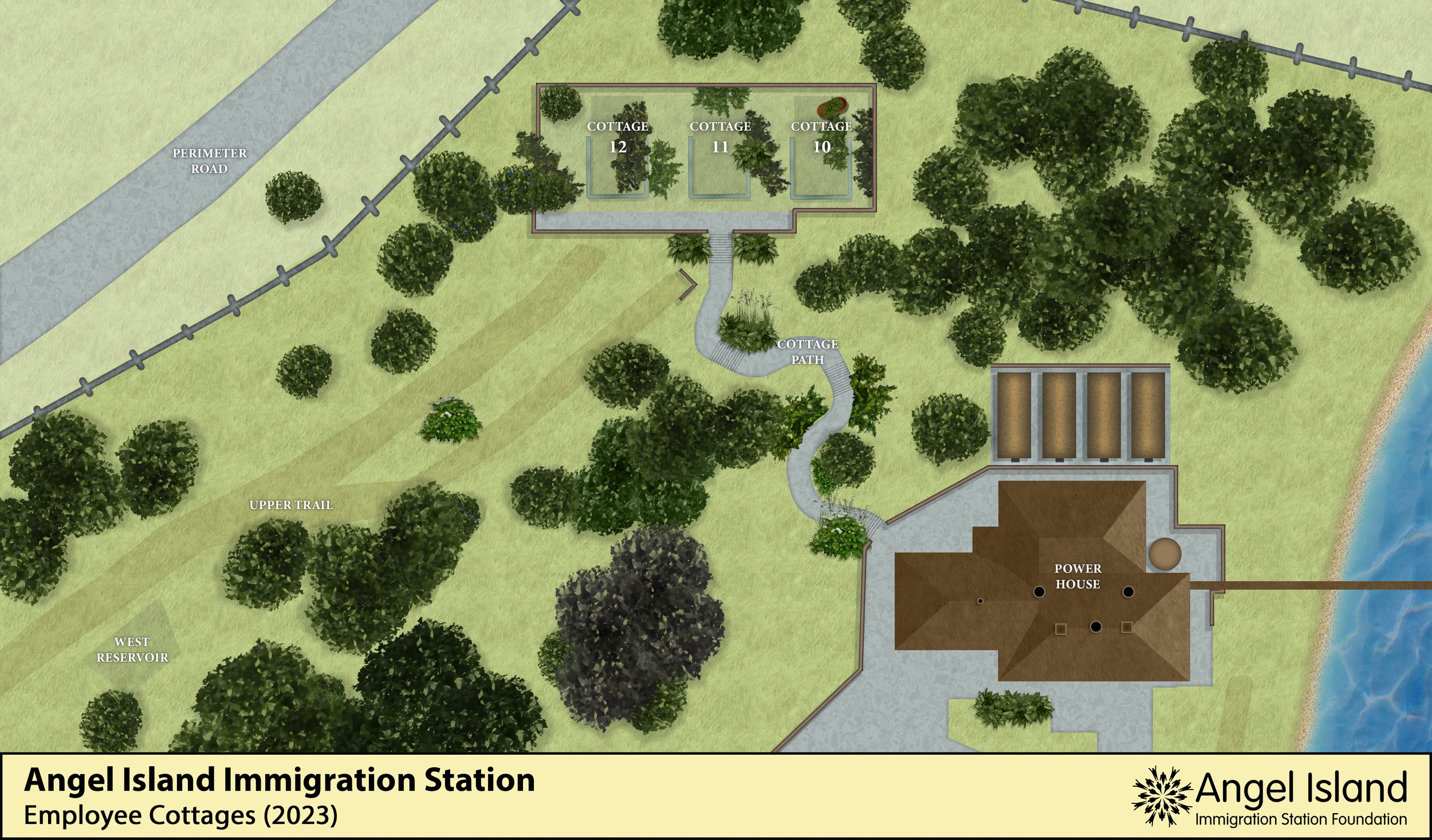

Cottages 10-12

When cottages 10, 11, and 12 were completed, they offered commanding views of the hospital, administration building, detention barracks, and the Immigration Station’s wharf. However, the cottages’ location behind the power house led to concerns about the safety of the structures and the hillside around them. Immigration Commissioner Luther Steward soon requested emergency funds to address these concerns.

“Remove the objectionable swampy conditions in some portions of the reservation caused by surface springs, and protect at least three of the recently erected cottages from landslides from the steep hill in their immediate rear, as well as providing walks, steps, and retaining walls in front, the latter being needed also as a protection from the bank giving way in several places in front of some of the cottages, with the possibility of undermining the structures.”

Cottage Paths

The Bureau of Immigration hired the Mahoney Brothers in July 1911 to complete sidewalks for the cottages. The Brothers were best known for building ten cable cars for the Ferries and Cliff House Railway in 1887. Cable cars 17, 23, and 27 were part of their fleet.

They completed a sidewalk in front of the nine cottages and a small retaining wall on the west side of the path. They also built two flights of steps on either end of the walkway to connect with the road below. Additionally, a similar but shorter sidewalk was constructed for the three cottages. Connecting to this sidewalk, the Mahoney Brothers built a winding brick path between the cottages and the power house.

Employee Residents and their Families

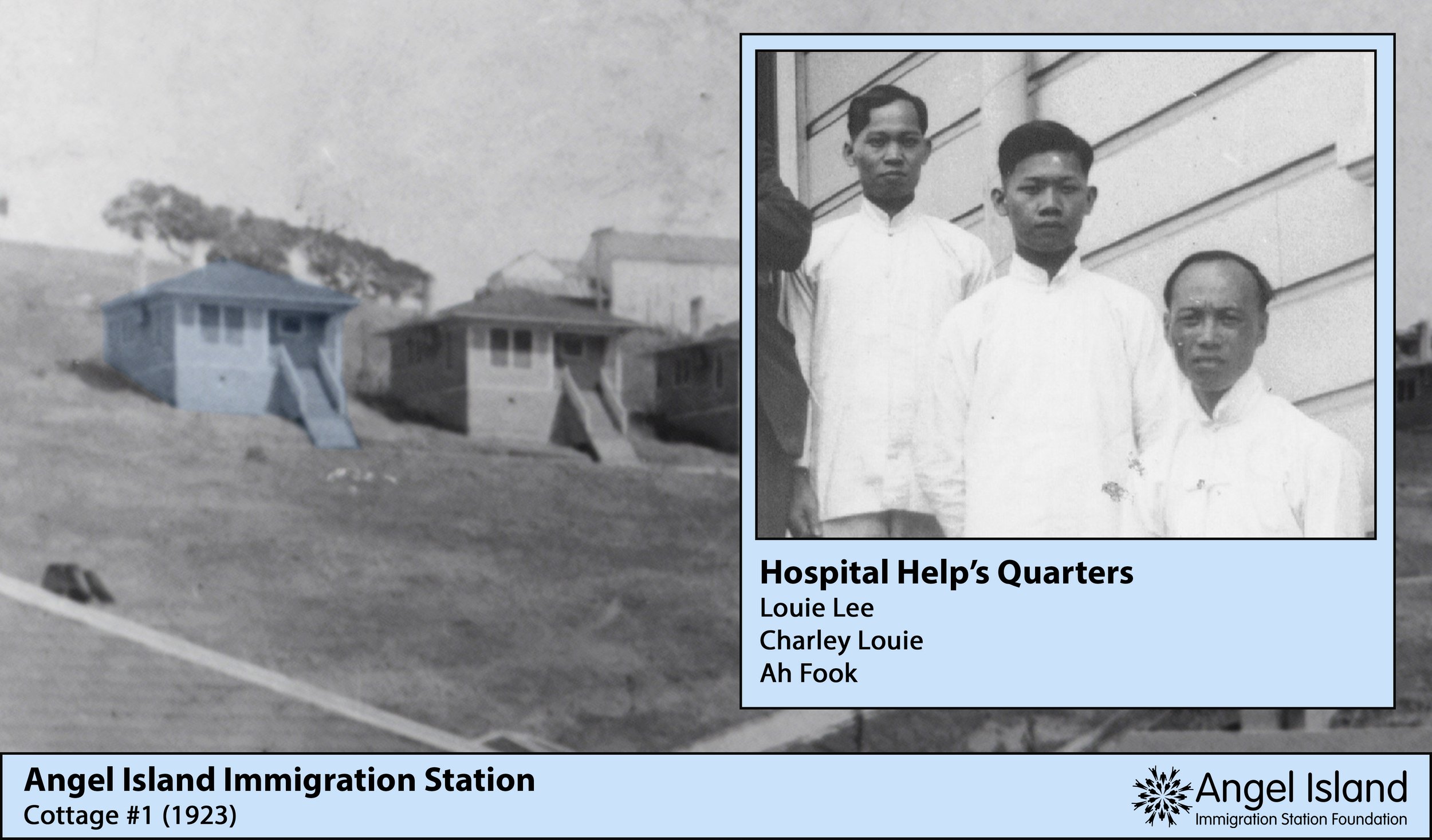

In June 1923, the Superintendent of Buildings issued recorded the residents of the Immigration Station, many of whom were photographed at the site.

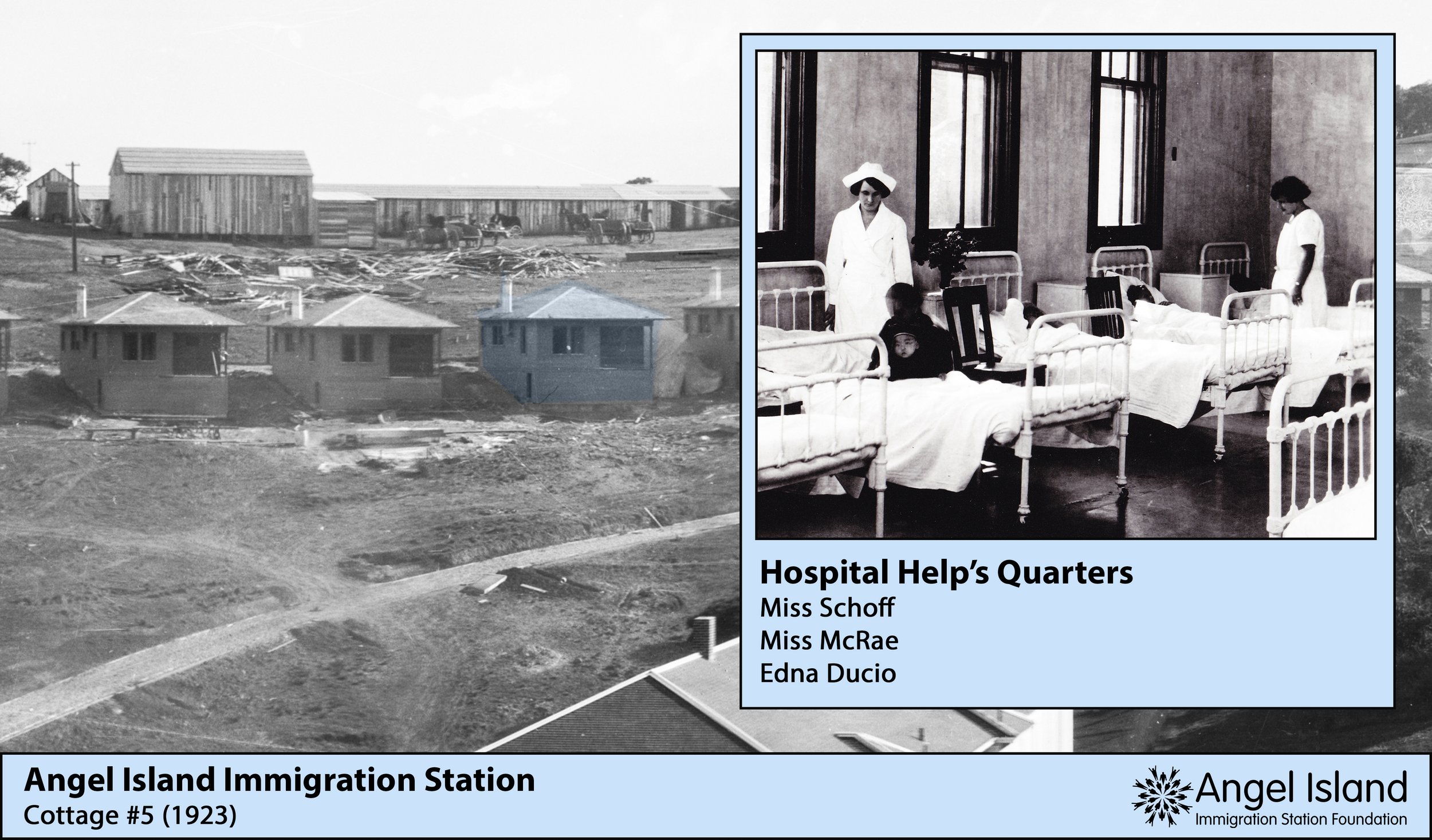

This photo from 1923 shows the residents of Cottage 1 (Louie Lee, Charley Louie, and Ah Fook), Cottage 2 (John Kelleher, Robert Stevenson, and Min Cho), and Cottage 5 (Miss Schoff, Miss McRae, and Edna Ducio). Eight of the residents are dressed in white. Edna Ducio, the hospital’s charwoman, is seated, dressed in black. NARA.

Employee Cottages

Hospital Help’s Quarters

Its proximity to the hospital made cottage one a suitable residence for the Public Health Service. Census records show it was used by the hospital’s Chinese cooks and servers.

Hospital Help’s Quarters

Like its neighbor, cottage two was a “bachelor’s quarters” for the hospital's white and Korean male attendants. It was the only residence where white and non-white employees slept under the same roof. See additional photographs of the hospital staff at Vault #14: A Closer Look.

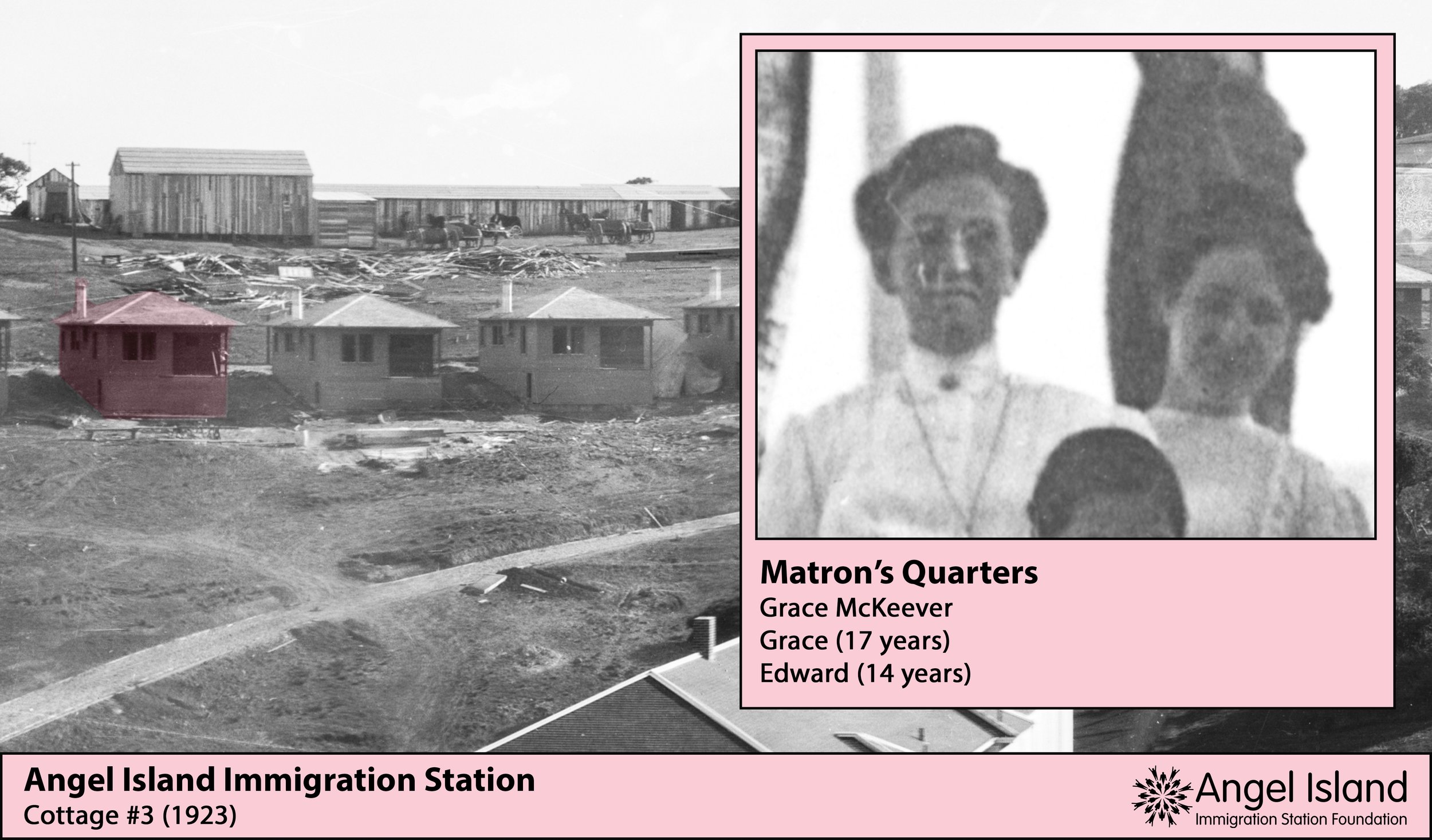

Matron’s Quarters

Although a matron’s residence was inside the administration building, Ms. McKeever lived in cottage three with her teenage daughter and son. Census records indicate that she was a widow.

Restaurant Help’s Quarters

Restaurant staff lived in cottage four. At least seven Chinese workers (cooks and dishwashers) slept in the two-bedroom cottage, while the restaurant’s white workers (servers) slept in the mule barn. Learn more about the restaurant staff at Vault #9: The Restaurant.

Hospital Help’s Quarters

Cottage five was the third and final cottage for Public Health Service employees. Records show that it was the residence of the hospital’s female nurses and charwoman.

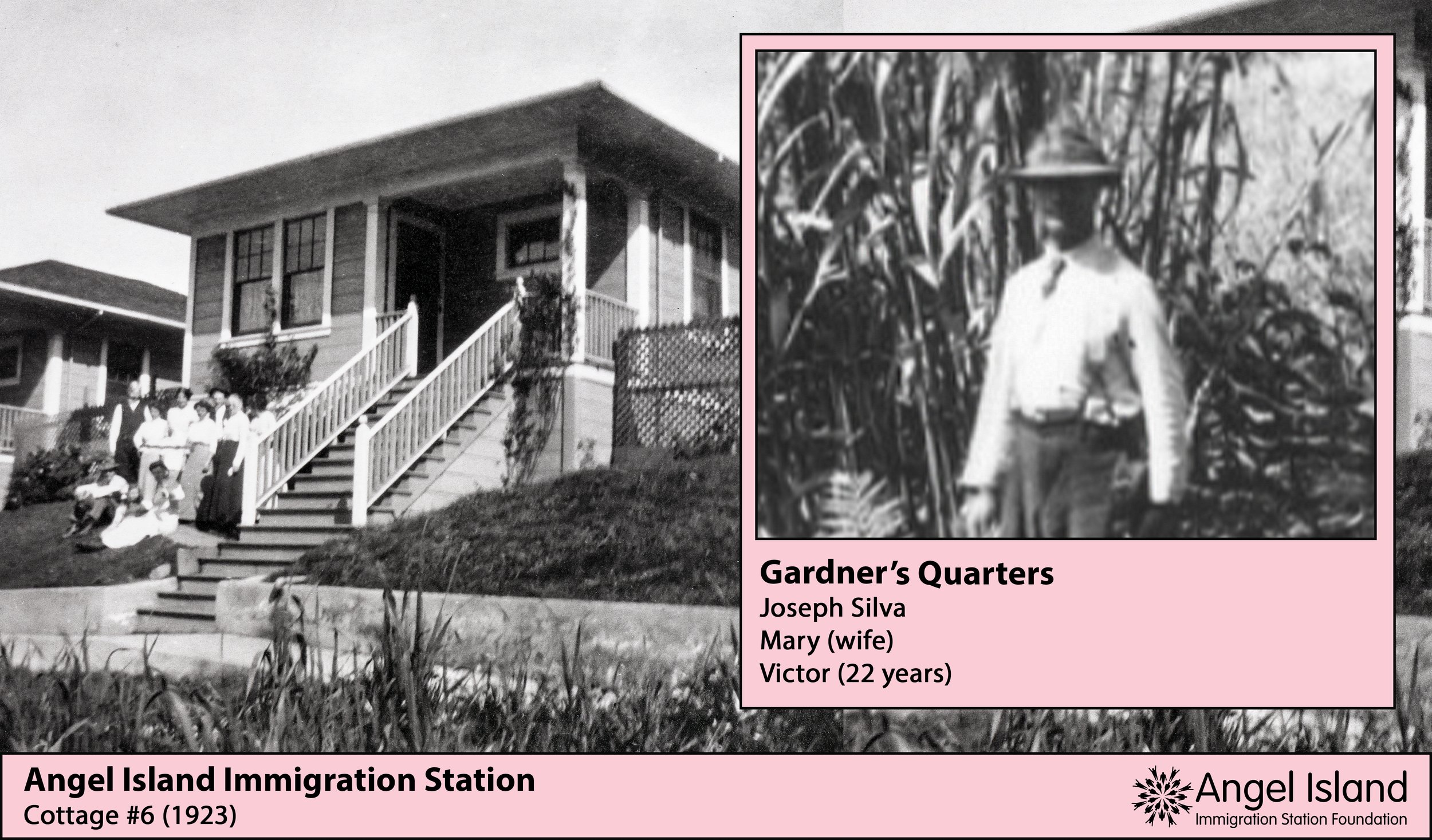

Gardener’s Quarters

The Station’s gardener, Joseph Silva, lived in cottage six with his family. Silva was born in the Azores islands, in Portugal, before immigrating to the US in 1892. Learn more about Mr. Silva at Vault #10: Historic Landscape.

Engineer’s Quarters

Alonzo Peery was one of the Station’s engineers. He lived in cottage seven with his wife and three kids, Norman, Victor, and Warren. The Peery family was close to the other engineers’ families at the site. Alonzo’s three boys played with the Thau, Garcia, and Mooney children.

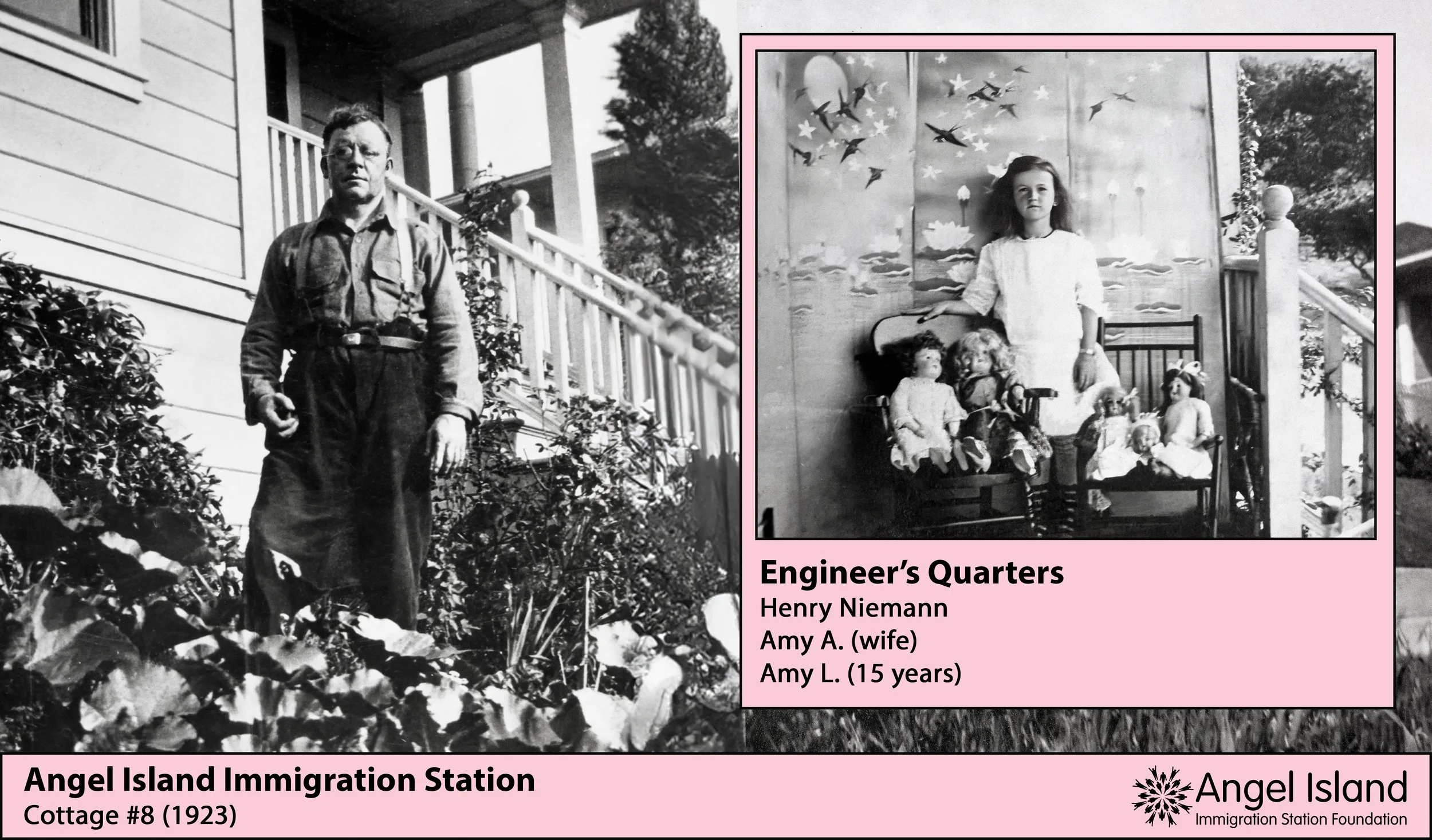

Engineer’s Quarters

Henry Niemann, his wife Amy, and his daughter Amy Lilly occupied cottage eight. Henry was one of the Station's engineers. The Niemann family had an affinity for lilies, as evidenced by Henry's daughter's middle name and two photos—one showing Amy Lilly posing with a waterlily backdrop and one of Henry in a flower garden, surrounded by lilies. Belladonna lilies can still be found in his yard each summer.

Engineer/Electrician’s Quarters

The Thaus lived in cottage nine. Albert Thau was the Station’s electrician. He lived on Angel Island for 14 years with his wife, Elizabeth, and two boys, Charles and Willard. Several photographs show Charles and Willard playing around the site and celebrating Christmas with Chinese immigrants.

Laborer/Truck Driver’s Quarters

The cottage closest to the water was occupied by the Immigration Station’s driver, Charles Richards, for nearly 20 years.

Laundryman’s Quarters

The Garcias, a family of five from Puerto Rico, lived in cottage eleven from 1923 to 1926. Philip Garcia worked as the Station’s laundryman.

Chief Engineer’s Quarters

The Mooneys made cottage twelve their home for many years. Hugh Mooney was an Irish immigrant and the chief engineer of the power house. Hugh’s wife, Mary, was a devoted mother to seven children. In 1930, the children’s ages were recorded in the US Census: Alice (16), Delores (16), Charles (13), Cyril (11), Kathleen (9), Eugene (7), and Barbara (5). By 1940, they had lived on Angel Island for 20 years.

1. Philip Jr. and Bernice Garcia; 2. Warren Peery, Philip Garcia Jr., Victor Peery, and Albert Garcia; 3. Bernice and Albert Garcia; 4. Philip Garcia Jr., Victor Peery, and Albert Garcia; 5. Bernice and Philip Garcia Jr.; 6. Alice, Kathleen, Delores, Charles, and Cyril Mooney. The photos shown here were donated to AIISF by the Garcia and Mooney families.

Living at the Immigration Station

Garcia Family

Philip Garcia’s children, Bernice and Philip Jr. were interviewed by AIISF in 2001 about living on the island. They recalled playing with other children and Baldy, the dog owned by the hospital’s superintendent. When asked about their house, Bernice and Philip recalled the following.

“We don’t remember anything particular about the house. It was not furnished and was pretty plain. We brought our own furniture. There was electricity, and there was a flush toilet and running water. It possibly had three bedrooms, but we don’t really remember our sleeping arrangement. When our father would catch fish, he would keep it on ice in the bathtub.”

“We played in the immediate area behind the house. We didn’t really wander off too far and were not allowed to go to very many places around the station. We did go to the docks and the beach but couldn’t run around or make a lot of noise.”

Mooney Family

By 1940, the Mooneys had lived on Angel Island for 20 years. In a 2001 interview with AIISF, Alice, Kathleen, and Eugene recalled what it was like for a family of nine living in a 653ft² cottage.

“It was very small just four rooms. We’d share a bed. They added a back to the house for the boys. We three girls were always in the same bedroom. We had a garden for flowers and vegetables sometimes. There was a crabapple tree. We were forbidden to eat the crabapples. If our father saw us eat the apples he’d give us a dose of castor oil.”

“[Going to school] we took the ferry—the Angel Island—back to the mainland... That was a long trip. We were always ten minutes late for school and always left ten minutes early so we were the envy of our classmates.”

In 1979, Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung interviewed Mary Mooney, the children’s mother. She recalled life on the island, including an incident in which an immigrant escaped from the detention barracks.

“When we first lived [on Angel Island], my girls were seven years old. On Saturday morning, they got up and came into my husband and my bedroom and said, ‘A man just went up the backyard and up the hill.’ In due time, they found a Chinese man in the water close to the island. He was trying to escape, but where he could escape to, I don’t know, because he couldn’t get off the island… When my husband went down to the building, they had taken a count and there was one [detainee] missing. They searched the island and didn’t find anyone. Then, within a week, they found the person in the water.”

One of the employee cottages engulfed in flames in 1971. Wooden supports from the porch can be seen on the right. Photo credit: California State Parks, Statewide Museum Collections Center (A-18, Tray 15).

Down in Flames

After the Immigration Station closed, the US Army took over the site and repurposed the cottages for non-commissioned officer (NCO) quarters. The Quartermaster General inventoried each building in December 1940, shortly before the army occupied them in 1941. Once WWII ended, the military abandoned the former Immigration Station, including its twelve cottages.

By 1971, the employee cottages were derelict after decades of disuse and neglect. Without the ability to save the 12 cottages, coupled with the risk they posed to visitors, Angel Island State Park decided to burn them in a fire training exercise. Footage of the fire was used in the 1972 film The Candidate, starring Robert Redford.

From the Ashes

The locations where Julia Morgan’s cottages once stood have been relatively untouched since 1971. Melted glass, electrical outlets, and various plumbing fixtures (sinks, faucets, and clawfoot tubs) are all that remains of the twelve employee residences.

In late 2023, with the support of San Francisco Assemblymember Phil Ting, the Immigration Station secured a $1 million state grant to rebuild one employee cottage at the site. Click here to read the announcement.

A quick note to visitors: Please use caution when exploring unmaintained areas of the Immigration Station. The cottage foundations are surrounded by uneven terrain and hidden hazards like pits, broken glass, and poison oak.

Architectural Resources Group and Daniel Quan Design. “Final Interpretive Plan,” December 2005.

Davidson, Mark and Quan, Daniel and Moore, Darci. Interview with the Garcia Family: Philip Garcia Jr. and Bernice Garcia, 2001.

Davidson, Mark and Quan, Daniel and Moore, Darci. Interview with the Mooney Family: Kathleen Keegan, Eugene Mooney, and Alice Curran, 2001.

Lee, Erika, and Judy Yung. Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

NARA. Correspondence from Commissioner Hart Hyatt North to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, June 30, 1908.

NARA. Correspondence from Commissioner Hart Hyatt North to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, December 10, 1909.

NARA. Correspondence from Acting Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, December 19, 1910.

NARA. Correspondence from Acting Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, February 1911.

NARA. Correspondence from Acting Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, July 19, 1911.

NARA. Correspondence from an Immigration Inspector to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, February 23, 1912.

NARA. Memorandum from the Superintendent of Buildings to the Commissioner of Immigration, June 4, 1922.

NARA. Correspondence from Commissioner John D. Nagle to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, August 16, 1932.

NARA. Correspondence from Acting Commissioner Edward Haff to the various cottage residents, November 25, 1932.

NARA. United States Census for the US Immigration Station, 1930.

Yung, Judy and Lai, Him Mark and Lim, Genny. Interview with Wife of a Maintenance Man, October 4, 1979.