Vault #9: The Restaurant

Inequity, Protests, and Dining on Angel Island

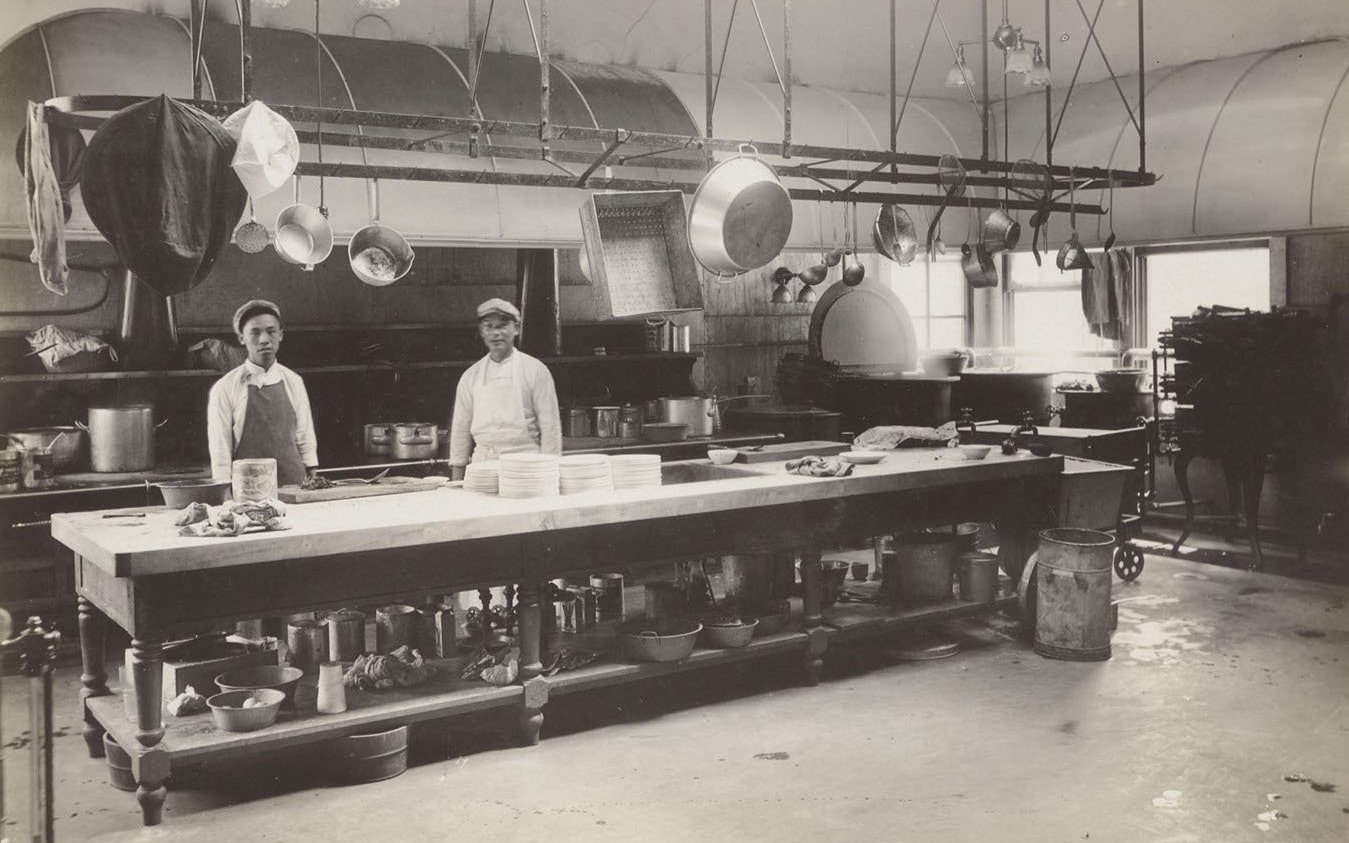

To work the long hours required for the job, kitchen staff were given housing at the Immigration Station. Many took advantage of living on the island to avoid high housing costs off-island and early work commutes. By 1923, the Bureau of Immigration housed seven Chinese kitchen employees in Cottage #4 and seven white kitchen employees in the former mule barn near the Immigration Station’s gate. Photo credit: NARA, Washington, DC, c. 1910.

Isolated from the conveniences of San Francisco, the Angel Island Immigration Station was built with large facilities equipped to handle the daily needs of those who lived, worked, visited, or were detained on the island. One of these facilities—the restaurant—was centrally located at the site and was responsible for feeding thousands of people between 1910 and 1940.

The restaurant occupied an entire wing of the main administration building and included a kitchen, dish closet, store rooms, pantries, dining rooms, and a small dormitory for its workers. Although commonly referred to as a “restaurant,” it operated more like an army mess hall, preparing approximately 3,000 meals each day.

Below, you’ll discover more information about the facility, its workers, and stories from former immigrants and officers that have shaped our understanding of the restaurant and the populations it once served.

The restaurant had an enclosed stairway that connected immigrants to the men’s barracks and an enclosed porch that led to the women’s dormitories on the second floor. This rendering shows the restaurant facilities based on architect Walter Mathew’s 1906 plan, positioned in its original location. Photo credit: AIISF, 2023.

Tales from the Kitchen

The restaurant’s staff played an important role in caring for immigrants’ nutritional well-being over the Station’s 30-year history. Rather than working for the Bureau of Immigration, they were hired by an independent contractor, which meant they received less pay and fewer accommodations than civil service employees. Unlike other Immigration Station staff, they were required to work long hours, preparing breakfast before the first ferry arrived in the morning and staying late to clean the kitchen after the site closed for the day.

In planning the restaurant, the Bureau gave little thought to the needs of its staff. The architect’s original plans proposed an eight-bedroom apartment above the Asian dining room, but his idea was later scrapped as a cost-saving measure. Instead, workers were crammed into a one-room dormitory directly above the food pantries. Dr. Glover, the Station’s surgeon, noted the dormitory was “totally inadequate,” mentioning that eight men shared a room that was only suitable for two people and it had no shower or bath.

Following Dr. Glover’s report, the cooks, servers, and helpers were temporarily moved to a former baggage room until other arrangements could be made. A year later, the Bureau issued a memo accusing the restaurant’s Chinese workers of colluding with detainees, which prompted another move at the site.

“The housing of Chinese cooks and helpers in the main building, close to the detention quarters, may have led to facilitating the ‘underground’ communication with detained Chinese. Assuming such help is a necessity, these persons should at least be segregated as far as possible from the Chinese whose cases are under investigation; hence the proposition of putting them in a cottage, where they can be kept under observation to better advantage.”

As a result of the Bureau’s suspicion, the district commissioner tightened security around the workers’ movement on and off the island. Officials also searched Chinese workers when they returned to Station and prohibited them from speaking to detainees during meals.

A coaching note that was hidden inside an orange. Photo credit: Board of Foreign Missions of the Methodist Episcopal Church, c. 1925.

Offering Hope to Detainees

Kitchen workers remained sympathetic to Chinese immigrants despite these restrictions and helped them whenever possible. Sometimes, they would take the ferry into San Francisco and retrieve coaching notes that helped “paper sons and daughters” prepare for their interrogations. These notes were essential for Chinese detainees to prevail against the government’s exclusionary immigration laws and racist practices.

Coaching notes were wrapped in foil or wax paper and hidden inside oranges, bananas, cookies, and specially-prepared dishes for the Gee Gee Wui, a self-governing organization formed by the Chinese to support fellow immigrants.

If the guards confiscated a note, it was the responsibility of other Chinese detainees to get it back. Anyone found in possession of these coaching notes was deported.

The tables in the Asian dining room were set with large earthenware serving dishes, crackers, chopsticks, and rice bowls. According to a Mary Bamford, author of the 1917 book Angel Island: The Ellis Island of the West, signs on the walls instructed Chinese immigrants “to not make trouble, nor spill food on the floor.” During holidays and other special occasions, the dining room was transformed into a social hall where immigrants could watch movies and listen to musicians. Photo credit: NARA, Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1910.

A Question of Equity

Like other areas of the site, the restaurant segregated races and classes among its dining rooms. Chinese and Japanese immigrants were separated from European (white) immigrants, and men were separated from women. Mrs. Woo, detained on Angel Island in 1940, remembered her experience visiting the restaurant in an interview with historians Him Mark Lai and Judy Yung.

“When we ate, they opened the doors electrically, so we couldn’t get out [at other times]… Even when we ate, we were separated. When they called you to dinner, they counted you. ‘One, two, three,’ in Chinese. After dinner, they counted you again… They treated us like criminals, which really wasn’t very nice if you had to stay long.”

From table settings to food options, white immigrants experienced better conditions than non-white immigrants. In fact—the entire restaurant was modeled after Ellis Island, which was built to serve mostly Europeans. In a 1910 memo, Commissioner Luther Steward criticized the Bureau for wasting money on kitchen equipment unsuitable for Angel Island. His complaint highlights the preferential treatment given to some immigrant groups over others.

“$1,737.70 was expended for installation of a bake-oven, in which I am told heat has been generated once. On account of the overwhelming proportion of non-bread-eaters among aliens detained at this station, bread consumption does not exceed twenty-five loaves per day. There is, accordingly, no use for such an oven and equipment, and never will be unless the character of immigrants arriving at this port undergoes a radical racial change.”

A former Angel Island interpreter echoed the commissioner’s sentiment by describing its effect on detainees.

"The unfortunate situation was when they built the kitchen, they weren't thinking of Chinese people coming to the station. They were building a kitchen suited for serving American food or large quantities for the army. So, they had a lot of steamers instead of [a] wok. You can just imagine cooking Chinese food without a wok. It was a very difficult situation. They would buy the cheapest rice and steam it in these big steaming kettles. The applicants got mad and said the food was uneatable."

This inequity was noticed not only by officials but by others as well. Michi Kawai, a general secretary of the YWCA in Japan, visited the Immigration Station three times to investigate conditions on the island. She published her findings in a report titled “A Day at Angel Island” in September 1915.

“When the lunch bell rings, [Japanese women] go downstairs to the dining room along with the Chinese, Spanish, and European women—all housed in separate quarters. The room is bare, save for eight rows of long tables and benches. On each table is a large pan filled with slices of bread, some small bowls of jam and white sugar, and cups for tea. The Europeans have meat, beans, and even better silverware. Only a few of the Japanese women are served one or two extra dishes, which they had ordered and purchased beforehand. Within five minutes, they finish eating and head back upstairs. At four o’clock for their supper they have steamed Chinese rice and greens cooked with scraps of pork in a salty broth. Some of the Japanese women tell me with tears that the food is awful.”

In contrast to Kawai’s report, French immigrant Jean Gontard described more favorable conditions from his brief detainment in 1914. Gontard’s description of the Station’s “dining hall” likely reflects the conditions of the European dining room since many Asian immigrants remember the cleanliness of their dining room as generally poor.

“The miserable troupe of women was conducted to the dining hall before large, clean, beautiful tables. The government does these things well. The Chinese received their rice. To the others was given meat, mashed potatoes, salad, coffee, in brief a good enough menu if it were not seasoned with so many anxieties and tears.”

A 1912 article from the San Francisco Call describes European meals costing 45 cents per plate, while “Asiatic” meals cost 33 cents. These charges were covered by steamship companies unless an immigrant appealed their case to a higher court. Then, the detainee would be responsible for all future charges. Photo credit: AIISF, 2020.

The meals listed below appear in a November 2, 1909 restaurant contract issued by the Bureau of Immigration. It illustrates a significant disparity in food options given to Angel Island’s two predominant immigrant groups.

European Meals

Breakfast

(a) Boiled rice, oatmeal, farina, cracked wheat, or cornmeal mush, served with the necessary milk and sugar or sirup (sic).

(b) Meat hash or baked pork and beans. Fried fish in lieu of meat hash or baked pork and beans on such days as may from time to time be officially designated.

(c) Fresh bread, spread with wholesome butter.

(d) A bowl of tea or coffee (the individual aliens' preference being consulted) with milk and sugar, served separately.Dinner or Midday Meal

(a) Vegetable, pea, bean, lentil, tomato, ox-tail, or macaroni soup.

(b) Fresh bread, spread with wholesome butter.

(c) Roast or fried beef, pork or mutton, or corned beef, served with mashed potatoes, peeled baked potatoes, or peeled boiled potatoes and one other vegetable-lima beans, mashed turnips, carrots, peas, corn, or succotash. For those who prefer, Kosher meat or fish, with potatoes and one other vegetable as above. Fresh fish, baked or boiled, in lieu of roast or fried meat, on such days as may from time to time be officially designated.

(d) A bowl of tea or coffee (the individual alien's preference being consulted), with milk and sugar, served separately.Supper

(a) Beef stew, mutton stew, baked pork and beans, or meat hash.

(b) Stewed prunes, apple sauce, pie, bread pudding with raisins, rice pudding, or tapioca pudding.

(c) Fresh bread, spread with wholesome butter.

(d) A bowl of tea or coffee (the individual alien's preference being consulted), with milk and sugar, served separately.Asiatic Meals

Breakfast

Bean soup, boiled rice, relishes, bread and tea; and in cases where Chinese are among the detained, boiled beef, pork or fish to be supplied upon request.Midday Meal

Boiled rice, cooked vegetables, with fish or meat, or salt salmon, pickles, bread, tea.Evening Meal

Boiled rice, cooked vegetables with fish or meat, or salt salmon, pickles, bread, tea.

This is the only known photograph of detainees eating in the Asian dining room. The room had 33 long tables that sat six to eight people each. Courtesy, California Historical Society, CHS2010.307.

Hunger and Growing Frustrations

Despite having a better meal selection than Asian immigrants, Europeans lamented their food was cold and changed very little. They also considered the frequency of beans being served as “objectionable.” In 1917, a group of German enemy aliens lodged a formal complaint against the Immigration Station with the Swiss Legation of San Francisco, which created additional problems for the Bureau.

For Asians, the lack of food variety led the Gee Gee Wui to solicit help from cooks and their connections in Chinatown. Their advocacy created a mutual aid network, resulting in extra food like lap cheong (Chinese sausage 臘腸) that could be steamed on the barracks’ radiators. Angel Island immigrant Richard Jeong Jew explained how the kitchen responded to their requests.

“One day we were told by some older men that we can eat congee free of charge at 6:00 p.m… I found out those men had raked up some traps to catch quails through the fence. They cleaned and chopped them up like hamburger, handed it to the guard. The Chinese cooks furnished rice to prepare it for us. I just remembered eating quail congee one time. Maybe they had killed all the quails on the Island or the guards had stopped the illegal operations.” Visit Vault #21 for stories about catching quail in detention.

If immigrants didn’t have money to purchase extra food, they faced insatiable hunger and malnourishment. Appearing physically weak in front of immigration officers placed detainees at risk of health-related deportations or created additional barriers between detention and freedom.

A Chinese poem in Room 105 of the barracks reveals how hunger made some individuals long for home.

Bidding farewell to the wooden building, I return to Hong Kong.

From hence forward, I will arouse my country and flaunt my aspirations.

I’ll tell my compatriots to inform their fellow villagers.

If they possess even a small surplus of food and clothing,

They should not drift across the ocean.

A Boiling Point

On New Year’s Eve 1920, 260 Chinese detainees staged a 7-day hunger strike and boycott over the quality of food and the restaurant’s steward, G.M. Echols, who brandished a gun when they refused to eat. According to the San Francisco Call, the boycott proved costly for the Station’s concessionaire.

“John Rothschild & Co. has the concession for a commissary store at the station. Immigrants and those held for deportation may purchase anything at the store from a postage stamp to a suit of clothes… The Chinese patronage of the commissary has been worth of late about $90 a day, it is said. When the boycott was declared, not one Chinese bought a penny’s worth of goods.”

Days after the boycott began, approximately two dozen newly arrived Chinese immigrants temporarily broke the strike until their compatriots stopped them. Guards intervened and moved the men into the Japanese quarters for their protection. The situation eventually resolved itself after an agreement was reached between the boycotters, Commissioner White, and Echols.

From Resistance to Action

As the Bureau of Immigration ignored immigrants’ pleas for better food and conditions, detainees responded to their ambivalence with anger instead of apathy. This anger erupted in another protest in 1925. Mr. Low, a kitchen worker during the protest, said Chinese immigrants broke all the dishes and went on a three-day hunger strike. The Petaluma Daily Morning Courier reported that soldiers from Angel Island’s Fort McDowell came to the Station with fixed bayonets to calm the more than 125 protesters. The Courier’s reporting offers additional information on what led to the hunger strike.

“According to immigration officials the trouble was precipitated when a white waiter either shoved or struck a Chinese. Immediately there was an uproar, and cutlery hurled through the air, and one guard, John Anderson, was knocked unconscious when struck on the head by an iron cuspidor.”

As punishment for the broken dishes, the concessionaire temporarily closed the restaurant’s commissary to punish protesters and deprive them of snacks until the hunger strike ended.

Click here to see several commercial products appearing in this photo of the store—also known as the commissary. A calendar from John Demartini Co., Inc. Shippers and Distributors (seen at right) dates the photo to April 1928. John Demartini sold fruit near Pier 5 in San Francisco, the same pier where Immigration Station employees boarded the ferry to Angel Island. Photo credit: California State Library.

The Commissary

The restaurant’s store sold fruit, candy, chewing gum, snacks, and other items from inside the Chinese and Japanese dining room. It introduced many immigrants to Western health and beauty products, packaged foods, and local flavors. The commissary’s assortment of ties, hats, mirrors, and razors helped immigrants appear more presentable at their Board of Special Inquiry hearing, and its tobacco, sport, and leisure-related items gave detainees ways to pass the time.

Many products in the commissary were marketed to men, which left female detainees increasingly dependent on Deaconess Katharine Maurer and the United Methodist Church for goods or activities. Missionaries frequently donated books, dolls, fabric, and sewing supplies to women and children, without which their detention would have been much more arduous.

The store was popular among immigrants, especially as an alternative to the restaurant’s unpalatable dishes. Indian immigrant Kala Bagai remembered visiting the commissary in 1915. Unlike other detainees, Kala’s family arrived on Angel Island with $25,000 in gold, some of which was spent on food.

“When the eating time came, they said ‘Chow, chow, chow,’ so I understood that means to eat. So I went over there. I didn’t like the food at all. But I saw that they were selling some fruits, so I bought some fruits. But I did not know how much money to give. So I took the money and put it in my hand... and let him take whatever he wants.”

Occasionally, coaching notes were sent to detainees through the commissary. Messages could be hidden more easily in fruit peels and packaged products than in regular menu items. Mr. Chew, detained on Angel Island in 1920, described a situation involving the store and a “paper daughter.”

“Someone got her some coaching notes. They snuck it in during mealtime by hiding it in some chewing gum. Another had a note wrapped inside a preserved plum. This person who gave her the plum said, ‘Look, there’s something in this plum, so pay attention.’ Another time, ‘There’s something in this candy, so be careful.’ Who knew that the white matron got suspicious and said, ‘What you got?’ The women got scared and started speaking in Chinese. That matron took the exact piece of chewing gum, plum, and candy. When they got back to the barracks, they became alarmed when they realized there was something in the sweets. So someone snuck back to that matron’s office and switched the gum, plum, and candy.”

Although the items Mr. Chew mentioned aren’t discernible in the photograph above, other products can be seen under closer inspection. Below is a list of items that has been identified by AIISF.

Apparel: bow ties; neckties; newsboy-style caps; pouches; suspenders

Bottled Goods: two drink varieties

Canned Goods: Booth’s Sardines; Monterey Salmon

Dry Goods: National Biscuit Company Ginger, Lemon, Chocolate, and Vanilla Snaps; Sun-Maid Seedless Raisins; packaged wafers/cookies

Hygiene: Colgate’s Rapid-Shave Cream; Kotex Sanitary Napkins; Superfine straight razor; Valet Auto Strop Razor; Van Camp’s soap; shaving mirror; talcum powder

Miscellaneous: Icy-Hot Bottle; baked goods; sharpener; softballs/handballs; suitcase; sundries

Oral Care: Colgate’s Ribbon Dental Cream; dental/tooth powder; toothbrushes

Produce: miscellaneous fruit

Tobacco Products: Bull Durham Smoking Tobacco; Camel Cigarettes; Chesterfield Cigarettes; Le Roy Cigars; Lucky Strike Cigarettes; Prince Albert Crimp Cut Long Burning Pipe and Cigarette Tobacco; Velvet Pipe Tobacco; Canadian-style pipe

Today, picnic tables are installed where the Asian dining room once stood. However, the concrete foundation seen here was built for the Post Exchange building (US Army store) in 1941. Click here to find this location on Angel Island. Photo credit: AIISF, 2022.

Architectural Resources Group and Daniel Quan Design. “Final Interpretive Plan,” December 2005.

Bamford, Mary. Angel Island: The Ellis Island of the West, The Woman's American Baptist Home Mission Society, 1917.

Bagai, Rani. Bridges Burned Behind. Excerpt from a November 26, 1982 interview.

Gontard, Jean. A Travers la Californie, 1922.

Jew, Richard Jeong. Story of the Water Buffalo from Hong Kong, 1996.

Kawai, Michi. A Day on Angel Island, Joshi Seinenkai, translated by John Akiyama, September 1915.

Lai, Him Mark and Laura. Interview with Mr. Chew, December 13, 1976.

Lee, Erika, and Judy Yung. Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

NARA. Correspondence from Dr. Melvin Glover to the Acting Commissioner of Immigration, November 21, 1910.

NARA. Correspondence from Commissioner Luther Steward to the Commissioner-General of Immigration, December 19, 1910.

NARA. Correspondence from the Commissioner-General to the Commissioner of Immigration, Angel Island, December 14, 1912.

NARA. Correspondence from the Superintendent of Buildings to the Commissioner of Immigration, June 4, 1923.

Petaluma Daily Morning Courier. "Troops Stop Chinese Riot," Volume 66, Number 114, July 2, 1925.

San Francisco Call. "Immigrants Must Pass Rigid Tests to Enter Golden Gate," April 14, 1912.

San Francisco Chronicle. "San Francisco to have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World," August 18, 1907.

Wong, Eddie. Interview with Frank Lum, February 18, 2011.

Yung, Judy and Lai, Him Mark and Laura. Interview with Mr. Low, December 27, 1975.

Yung, Judy and Lai, Him Mark. Interview with Mr. Ng, January 5, 1976.

Yung, Judy and Lai, Him Mark. Interview with Mrs. Woo, June 19, 1977.

Yung, Judy; Lai, Him Mark; Lim, Genny; and Chow, Paul. Interview with Immigration Interpreters #1 and #2, May 8, 1976.